Australia has one of the weakest tax systems for redistribution among industrial nations – Stage 3 tax cuts will make it worse

Where does Canada rank on the global scale of income redistribution through taxation? Jim Stanford’s article on the gini coefficient provides answers

|

Jim Stanford is an economist and director, Centre for Future Work, Australia Institute, and honorary professor of political economy, University of Sydney. |

ONE of the chief purposes of government payments and taxes is to redistribute income, which is why tax rates are higher on taxpayers with higher incomes and payments tend to get directed to people on lower incomes.

Australia’s tax rates range from a low of zero cents in the dollar to a high of 45 cents, and payments including JobSeeker, the age pension, and child benefits which are limited to recipients whose income is below certain thresholds.

In this way, every nation’s tax and transfer system cuts inequality, some more than others.

Which is why I was surprised when I used the latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data to calculate how much.

The OECD measures inequality using what’s known as a gini coefficient. This is a number on a scale between zero and 1 where zero represents complete equality (everyone receives the same income) and 1 represents complete inequality (one person has all the income).

The higher the number, the higher the higher the inequality.

Australia is far from the most equal of OECD nations — it is 21st out of the 37 countries for which the OECD collects data, but what really interested me is what Australia’s tax and transfer system does to equalise things.

And the answer is: surprisingly little compared to other OECD countries.

Australia’s system does little to temper inequality

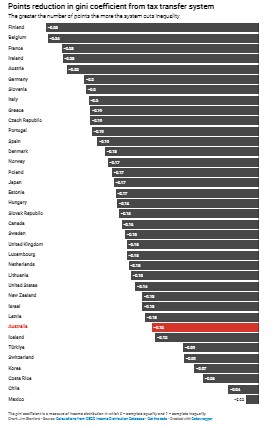

The graph below displays the number of points by which each country’s tax and transfer system reduces its gini coefficient. The ranking indicates the extent to which the system equalises incomes.

The OECD country whose system most strongly redistributes incomes is Finland, whose tax and transfer rules cut its gini coefficient by 0.25 points.

The country with the weakest redistribution of incomes is Mexico which only cuts inequality by 0.02 points.

Australia is the 8th weakest, cutting inequality by only 0.12 points.

Apart from Mexico, among OECD members only Chile, Costa Rica, Korea, Switzerland, Türkiye and Iceland do a worse job of redistributing incomes.

|

CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE. |

What is really odd is that, before redistribution, Australia’s income distribution is pretty good compared to other OECD countries — the tenth best.

It’s not that Australia’s systems don’t reduce inequality, it’s that other country’s systems do it more.

Of the OECD members who do less than Australia, four are emerging economies: Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Türkiye. Like most developing countries, they have low taxes, weak social protections and poor tax-gathering systems.

Indeed, in Chile and Mexico, taxes and transfers do almost nothing to moderate extreme inequality.

The other three countries ranked below Australia — Iceland, Switzerland, and South Korea — boast unusually equal distributions of market incomes. Each is among the four most equal OECD countries by market income, and each is considerably more equal than Australia.

Australia ‘less developed’ when it comes to redistribution

This makes Australia’s weak redistribution system more typical of a low-income emerging economy than an advanced industrial democracy.

Even Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand do a better job of redistributing income than Australia.

This new data enhances concerns about the impact of planned Stage 3 tax cuts. By returning proportionately more to high earners than low earners these will further erode the redistributive impact of Australia’s tax system.

It also highlights the consequences of Australia’s relatively weak payments programs, including JobSeeker which on one measure is the second-weakest in the OECD. It’s an understatement to say we’ve room for improvement.

Jim Stanford is an economist and director, Centre for Future Work, Australia Institute, and honorary professor of political economy, University of Sydney. Read the original article, with hyperlinks, on The Conversation Canada. Author photo, chart, courtesy The Conversation. Title image: Pixabay composite image.

(0) Comments