The Foix decision: The long and uncertain reach of subsection 84(2)

The broader interpretation by the Federal Court of Appeal in a tax case involving a complex hybrid sale was a breath of fresh air says Allan Lanthier

MONTREAL – In late February, the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) issued its decision in Foix,[1] a case that involved a complex series of transactions put in place to sell a Canadian business to an unrelated third party.

Upholding a decision of the Tax Court of Canada (TCC), the FCA concluded that funds or property of a Canadian corporation had been distributed or appropriated to or for the benefit of its shareholders, and that subsection 84(2) of the Act[2] therefore applied to deem some of the sale proceeds paid to the shareholders to be taxable dividends.

The planning involved safe income, the lifetime capital gains exemption (LCGE) and the capital dividend account. While the reasons for judgment do not include a complete recital of all the steps that were taken or the tax benefits the taxpayers were seeking from each step, the taxpayer’s Notice of Appeal filed with the TCC helps fill in some of the blanks.

While the facts in Foix are somewhat unusual, the decision is significant. The court stated that an anti-avoidance provision such as subsection 84(2) should be given a broad interpretation, and that the uncertainty and unpredictability that results is appropriate. This article discusses the decision, and the implications it may have in the context of other anti-avoidance provisions.

The facts

Mr. Foix and Mr. Souty met while doing consulting work for Videotron and, in 2000, they incorporated a Canadian corporation called Watch4Net Solutions Inc. (W4N). The company prospered: its main activity was the exploitation of proprietary software (called “APG”) that it had developed: it also provided IT advisory services. By 2012, W4N had about 50 employees, and annual gross revenue of $15 million.

EMC Corporation (EMC US), a US public corporation, was in a different league altogether. In 2012, EMC US had approximately 65,000 employees globally and annual gross revenue of US $13 billion. But it was always looking for acquisitions and growth. In 2006 it made an offer to purchase the shares of W4N for an amount of US $3 to $5 million: Messrs. Foix and Souty found the amount to be far too low and rejected the offer. Later, in 2011, EMC offered to buy an exclusive license of the APG software from W4N in exchange for annual royalties.

In early 2012, a deal was finally struck: EMC US or its Canadian subsidiary EMC Canada would purchase the shares of W4N, and the shares of Mr. Foix’s holding company (Holdco) which held shares of W4N, for an amount of US $50 million.[3] The tax advisors leapt into action.

The hybrid sale

In April 2012, the parties agreed to convert the transaction into a hybrid sale of W4N’s shares and assets: EMC Canada would purchase the shares of W4N and Holdco,[4] and EMC US, the parent company, would purchase most of W4N’s business and assets, including the APG software, contracts with customers (except for customers located in Canada) and goodwill.

The parties signed a Hybrid Sale Agreement on or around May 24, 2012. On May 30, Messrs. Foix and Souty completed share-for-share exchanges and received new shares of Holdco and W4N respectively, using election amounts of $750,000 under subsection 85(1) of the Act to crystallize capital gains sheltered by the LCGE.

The following four steps were then completed:

- Also on May 30, at 11:30 p.m., trusts for the families of Messrs. Foix and Souty sold a number of W4N shares to EMC Canada for $4,979,182.

- Fifteen minutes later, at 11:45 p.m., EMC US purchased the APG software and other assets from W4N for $44,050,000 million. As consideration, EMC US delivered two “Capital Dividend Promissory Notes” of $11 million each to W4N, and a “Balance Note” of $19,750,000. EMC US also assumed $2,300,000 of W4N’s liabilities.

- On May 31 at 12:15 a.m., EMC Canada purchased special voting shares of W4N for a nominal amount ($1,100), giving EMC Canada de jure control of W4N.[5]

- Fifteen minutes later, at 12:30 a.m., EMC Canada purchased the remaining shares of W4N, and the shares of Holdco, for $13,189,796.

The Capital Dividend Promissory Notes of $22 million were paid as dividends to the shareholders of W4N as part of the closing steps and elections filed under subsection 83(2) of the Act:[6] the notes were then settled by cash payment. The total cash amount received by W4N’s shareholders, including the cash of $18,170,078 received on the share dispositions in steps 1, 3 and 4 above, was therefore $40,170,078.[7] However, in what the court viewed as the most critical issue, the Balance Note of $19,750,000 was not paid at closing.

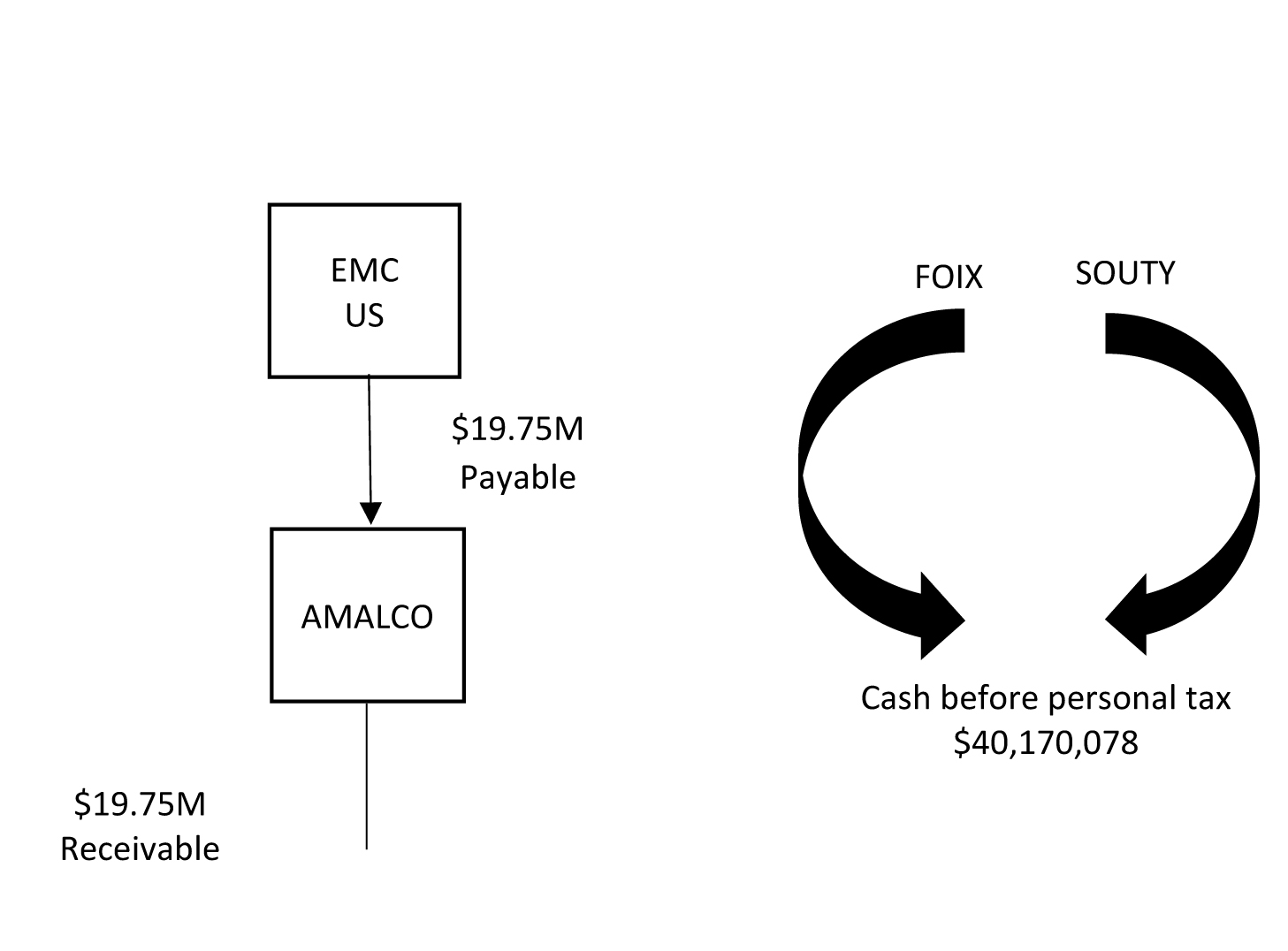

On June 1, the day following the hybrid sale, EMC Canada, W4N and Holdco amalgamated, leaving the final structure as follows:

|

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE. Chart provided by author.. |

The corporate tax rate on the asset sale

The corporate tax rate that applies to asset sales in hybrid transactions depends in part on the nature of the assets being sold, and whether or not the target corporation is a “Canadian-controlled private corporation” (CCPC) at the time of the asset sale.

In Foix, the Minister accepted the position that the assets were “eligible capital properties” (goodwill) and that the 50 percent income inclusion was therefore business income to W4N (taxed at the general federal-Quebec rate of 26.9 percent) rather than a taxable capital gain.[8]

Had the sale resulted in a taxable capital gain, the income would have been taxed at a much higher rate (about 46.6 percent, including refundable taxes), but only if W4N was a CCPC at the time of the sale.[9]

Accessing the lower corporate rate is critical to these types of hybrid sale transactions,[10] and one consequence of the new “Substantive CCPC” provisions is that the higher corporate rate now applies: as a result, these transactions are no longer viable.[11]

The issue in dispute

The Minister’s position was that subsection 84(2) applied to deem some of the sale proceeds paid to the shareholders of W4N to be taxable dividends.[12] Curiously, out of total cash proceeds of $18,170,078, the Minister only applied the provision to proceeds of $3,191,155 — representing some of the proceeds in steps 1 and 4 — in the words of the Minister, to “transform” capital gains for which the LCGE had been claimed into dividends.[13]

Subsection 84(2) reads, in relevant part, as follows:

“Where funds or property of a corporation resident in Canada have at any time after March 31, 1977 been distributed or otherwise appropriated in any manner whatever to or for the benefit of the shareholders of any class of shares in its capital stock, on the winding-up, discontinuance or reorganization of its business, the corporation shall be deemed to have paid at that time a dividend on the shares of that class equal to the amount, if any, by which

(a) the amount or value of the funds or property distributed or appropriated, as the case may be,

exceeds

(b) the amount, if any, by which the paid-up capital in respect of the shares of that class is reduced on the distribution or appropriation, as the case may be,” [Emphasis added]

In the FCA decision, Noël, C.J. stated that the taxpayers had correctly asserted that, for subsection 84(2) to apply, the target corporation (W4N) must be “impoverished” to the benefit of its shareholders and that, at some juncture, funds or property must leave the target corporation and end up in the hands of the shareholders. He then stated that, unless the Balance Note of $19.75 million owing by EMC US to W4N (and, after the amalgamation, to the successor corporation) was in fact paid, the funds that would have been used to pay the debt were in fact used to pay for the shares of W4N.

At trial, the taxpayers did themselves no favours. At the TCC, the only witnesses were Messrs. Foix and Souty, and W4N’s external accountant. No one from EMC testified. Boyle J. found key parts of the testimony of Messrs. Foix and Souty to be inconsistent with the Hybrid Sale Agreement, and stated that Mr. Foix was “difficult and evasive” during his cross-examination.

That frustration continued on appeal. Noël, C.J. stated that the “heart of the debate” was what became of the Balance Note: either the debt was paid or it was not. He added that “If it was, all that was needed is for the appellants to require the EMC group to produce the accounting entry confirming the payment”. In the absence of such evidence, Noël, C.J. concluded that it was open to the trial judge at the TCC to find, as he had, that the debt of $19.75 million evidenced by the Balance Note was used to fund the cost of W4N’s shares, thereby impoverishing W4N: as a result, subsection 84(2) applied.

Was the FCA’s conclusion justified? While W4N or its successor corporation may have been impoverished (and EMC US enriched) if the Balance Note was cancelled or extinguished for no consideration,[14] did the funds related to the Balance Note “end up in the hands” of the former shareholders of W4N as required for the application of subsection 84(2)?

I suggest that it was appropriate for the court to conclude as it did. Had EMC US paid the Balance Note of $19.75 million at closing, W4N would have been holding the cash at the time its remaining shares were purchased in step 4.[15] Whether W4N had cash of $19.75 million at closing or a Balance Note of the same amount, those assets were not required in its business: in fact, substantially all of its business had already been purchased by EMC US.

However, instead of causing W4N to pay taxable dividends of $19.75 million, its shareholders received the funds as proceeds of disposition for their shares, with the result that the funds owned by W4N related to the Balance Note did arguably end up in their hands. As a result, the Minister could have applied subsection 84(2) to the entire sales proceeds of more than $18 million received from EMC Canada, rather than restricting the assessment (as was done) to amounts that were relevant to LCGE deductions.

|

The Federal Court of Canada case, which was heard in Montreal and delivered in Ottawa, has implications for the interpretation of anti-avoidance provisions. (iStock) |

What are the implications of the decision?

While the FCA’s conclusion in Foix may be restricted to the somewhat peculiar facts involved, its reasons for judgment are significant.

Noël, C.J. took issue with recent court decisions, including the TCC decision in Robillard,[16] that have argued for a strict and textual interpretation of anti-avoidance provisions. At paragraph 82 of the decision, he stated that:

“…the appellants argue that the trial judge’s broad interpretation of subsection 84(2) makes the application of this provision unpredictable, uncertain and unfair, and that it should be rejected on that account. However, an anti-avoidance measure will necessarily raise question marks in the minds of those who choose to test its limits.”

Compare the above to the very first sentence in the recent 6-3 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) in Alta Energy,[17] in which the majority states that “The principles of predictability, certainty, and fairness for the right of taxpayers to legitimate tax minimization are the bedrock of tax law.” The decision was sixty-six pages long, but it was hardly necessary to read any further to know that the taxpayer had prevailed.

Alta Energy was a treaty-shopping case involving the sale of shares of a Canadian corporation to a shell company in Luxembourg to avoid tax on a capital gain of $380 million. The majority concluded that the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) did not apply and that the gain was therefore exempt from Canadian tax: its position was that a largely textual interpretation was appropriate having regard to the facts of the case and the relevant tax treaty provisions.

It is clear that, today, all statutes, including the Act, must be interpreted in a textual, contextual and purposive manner:[18] however, how much emphasis is placed on a textual rather than a broader interpretation will depend on the particular facts of each case and the statutory provisions involved.

In Foix, the FCA concluded that a broader interpretation was appropriate. This was a breath of fresh air: a broader interpretation will invariably strike a more reasonable balance between the rights of taxpayers and those of the Crown. However, only time will tell whether courts will now place a greater emphasis on a broader interpretation in the context of other anti-avoidance provisions.

Footnotes

[1] Foix, Souty and Lebel v. Canada, 2023 FCA 38.

[2] The federal Income Tax Act, RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended, referred to herein as the “Act”.

[3] At the time, the Canadian and US dollars were at par, and the transaction was ultimately implemented in Canadian dollars.

[4] Some of the shares of W4N were held by family trusts.

[5] As a result of steps 2 and 3, W4N ceased to be a “small business corporation” for purposes of the LCGE.

[6] W4N paid dividends of $11 million out of its capital dividend account (CDA) to each of Mr. Souty and Holdco, and Holdco then paid a CDA dividend of $11 million to Mr. Foix.

[7]The difference between the total cash received of $40.170 million and the agreed sales price of $50 million, is largely attributable to the facts that (i) EMC Canada would have assumed responsibility for the corporate tax of about $6 million payable by W4N on the asset sale, and (ii) EMC US assumed $2.3 million of W4N’s liabilities on that sale (increasing the amount of excess cash that W4N would have distributed to its shareholders before the other closing steps).

[8] This even though software is generally depreciable property, rather than eligible capital property. Effective January 1, 2017, the eligible capital property regime was repealed and a new class of depreciable property (Class 14.1) took its place.

[9] Under paragraph 251(5)(b) of the Act, W4N ceased to be a CCPC on or around May 24, 2012 when the Hybrid Sale Agreement was executed.

[10] Otherwise, the corporate tax on the asset sale plus personal tax on the sale of shares of the target corporation, will significantly exceed the personal tax that would have applied to a straightforward sale of shares.

[11] For a discussion of these new provisions, see “Substantive CCPCs: Is the tax deferral game over”; Allan Lanthier; Canadian Accountant; May 12, 2022.

[12] In the alternative, the Minister’s position was that the vendors and purchaser were acting in concert, and that section 84.1 of the Act therefore deemed the proceeds to be taxable dividends. Given the court’s conclusion that subsection 84(2) applied, it did not address section 84.1.

[13] Paragraph 22 of the FCA’s reasons for judgment. As explained earlier, Messrs. Foix and Souty had realized capital gains sheltered by the LCGE as part of share-for-share transactions on May 30, and the Minister treated the capital gains resulting from those exchanges, as well as smaller capital gains realized when the exchanged shares were sold to EMC Canada in step 4, as deemed dividends under subsection 84(2).

[14] If the Balance Note was cancelled for no consideration, a taxable benefit to EMC US of $19.75 million should have resulted (subsections 15(1), 15(2) or 246(1) of the Act) to which tax under Part XIII of the Act would apply.

[15] In this event, the successor corporation to the amalgamation of EMC Canada, W4N and Holdco would almost certainly have paid most of W4N’s cash to EMC US as a statutory reduction of paid-up capital, to allow EMC US to repay bridge financing.

[16] Robillard (Estate) v. The Queen, 2022 TCC 13. Robillard involved a post-mortem pipeline gone awry because the taxpayer had not respected the CRA’s one-year administrative position. In Robillard, Hogan J. discusses, and takes issue with, the FCA’s conclusion in MacDonald (2013 FCA 110), and argues for a narrow and textual approach of subsection 84(2). In Foix, Noël, C.J stated that, contrary to the TCC’s position in Robillard, the evolution of the provision since its adoption in 1924 “does not run counter to its broad interpretation”.

[17] Canada v. Alta Energy Luxembourg S.A.R.L, 2021 SCC 49.

[18] See for example Canada v. Canada Trustco Mortgage Company, 2005 SCC 54.

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm, and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. Author photo: courtesy Allan Lanthier. Image: iStock.

(0) Comments