Deans Knight: The return of the GAAR

The Supreme Court of Canada's decision in Deans Knight is a breath of fresh air and strikes a more appropriate balance, says Allan Lanthier

MONTREAL – Late last month, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) released its decision in Deans Knight.[1] At issue was a complex tax avoidance plan that sought to monetize a taxpayer’s non-capital losses and other tax attributes, while narrowly avoiding the acquisition of control restrictions in the Income Tax Act.[2] In a 7 to 1 decision, the SCC held that the plan was abusive and that the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR)[3] therefore applied to deny the tax benefits.

The court held that, while subsection 111(5) of the Act only denies the carry-forward of tax losses if de jure control of a corporation is acquired by another party (an event that had not occurred), a GAAR analysis requires a search for the legislative rationale for the denial, a search that may go beyond the bare meaning of the words themselves: in other words, the rationale for a provision will not always be fully reflected in its text. The court concluded that the plan carefully circumvented an acquisition of de jure control, while transferring the core control rights to a third party: as a result, the plan frustrated the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5).

This approach to a GAAR analysis — searching for the legislative rationale of a provision beyond its bare text — is a breath of fresh air, and should strike a more appropriate balance between the rights of taxpayers to plan their affairs, and the Crown’s ability to defend the integrity of the income tax system.

After describing the facts, the plan, and the provisions of the Act that were relevant, this article summarizes the court’s decision and discusses its possible implications.

The Facts

Forbes Medi-Tech Inc. (Forbes) was a publicly-traded Canadian corporation that was in the pharmaceutical research business. In 2007, Forbes was struggling and needed cash. The company had tax attributes of about $90 million — non-capital losses, SR&ED expenditures and investment tax credits — which it would likely never be able to use. The company, with the assistance of PwC, started reviewing alternatives to monetize the tax attributes.

The company received two proposals for a monetization, and settled on a plan from Matco Capital Ltd. (Matco), a privately-owned venture capital firm based in Calgary that had been involved in such transactions in the past. Under Matco’s plan, Forbes would receive cash of between $3.5 million and $4 million for its tax attributes — 4 to 4.5 cents on the dollar. The following steps were put in place:

- In early 2008, a new Canadian corporation (Newco) was incorporated and, under a court-approved plan of arrangement, all outstanding shares of Forbes were transferred to Newco on a share-for-share exchange basis. As a result, Forbes became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Newco, and the shares of Newco began trading on the TSX and NASDAQ in substitution for the common shares of Forbes.

- Forbes changed its name, and is referred to in this article as “Lossco” (as explained further below, Lossco changed its name to Deans Knight in 2009).

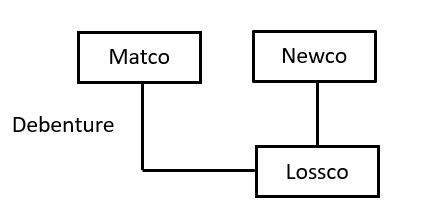

- Matco, Newco and Lossco then entered into an agreement (the “Investment Agreement”). Matco agreed to purchase a debenture from Lossco for cash of $3 million, convertible into 35 percent of the voting shares and 100 percent of the non-voting shares of Lossco (in total, comprising 79 percent of Lossco’s equity), and guaranteed that Newco could (but was not required to) sell its Lossco shares to Matco for a minimum amount of $800,000.[4]

- The Investment Agreement also provided that Lossco would be reorganized: its assets, liabilities and the cash paid by Matco for the convertible debenture, would be transferred to Newco, and Matco would have one year to present a “corporate opportunity”: a plan that would allow Lossco to start a new business, likely with different management, with the tax attributes to be applied against profits from the new business.

- The Investment Agreement was executed on May 9, 2008. Matco subscribed for the convertible debenture of $3 million, and Lossco transferred its assets and liabilities to Newco for a promissory note. Lossco then transferred the cash, and the promissory note payable by Newco, to a wholly-owned subsidiary of Newco.[5] When the smoke had cleared, the corporate structure was as follows:

|

CLICK TO ENLARGE. |

Newco (New Forbes) now carried on the pharmaceutical research business. And while Newco held 100 percent of Lossco’s issued and outstanding shares, Lossco (to use the words of the SCC) was gutted of any vestiges from its prior corporate life and became an empty vessel with tax attributes. Lossco was now waiting for a knight in shining armour to surface and use its tax attributes: but before we get to that, let’s review a few more details.

The Investment Agreement

The basic elements of the Investment Agreement are described above. But there were more: the agreement ensured that, even without de jure control of Lossco, Matco held all of the core control rights.

For example, Newco would use its best efforts to ensure that the only three directors of Lossco were its CEO, its CFO, and a representative selected by Matco: the CEO and CFO would resign following the acceptance of a plan to use the tax attributes.

Also, without the consent of Matco, Newco or Lossco could not engage in most activities that are normally in the domain of a corporation’s board of directors. These restrictions applied to actions such as the issuance, redemption or purchase of shares, the payment of dividends, and engaging in any activity other than examining and pursuing the “corporate opportunity” relating to the further $800,000 commitment made by Matco.

In summary (and again in the words of the SCC), the contractual restrictions in favour of Matco meant that, even though Matco did not acquire de jure control of Lossco, the powers of Lossco’s directors were effectively neutralized for the duration of the agreement.

Enter Deans Knight

The plan was in place. But Matco needed another party to do the heavy lifting: someone who would start a new business in Lossco, and generate profits to apply against its tax attributes.

In December 2008, Matco presented Lossco with a plan from Deans Knight Capital Management Ltd. (DKCM), a Vancouver-based asset management firm. DKCM would start a business in Lossco of investing in high-yield debt instruments, with the investments to be funded by an initial public offering (IPO) of about $100 million. Lossco would be the corporate vehicle for the IPO and become a publicly-traded corporation. Lossco agreed and, in early 2009, the plan was put in place.

Lossco’s name was changed to “Deans Knight Income Corporation” (Deans Knight) and, prior to the IPO, Matco converted its debenture into 35 percent of the voting shares and 100 percent of the non-voting shares of the re-named Deans Knight. The IPO closed in March 2009 and, immediately following the IPO, Matco (through a related corporation) made an offer to Newco to purchase its shares of Deans Knight for $800,000.[6] The offer was accepted.

As a result, Deans Knight was now a publicly-traded corporation, with no ongoing connection to Newco.[7] Matco remained a shareholder of Deans Knight, with shares in the corporation worth $4.5 million following the IPO.

In its tax returns for the years 2009 to 2012, Deans Knight deducted about $65 million of its tax attributes. The Minister disallowed the deductions, and it was left to the courts to settle the dispute.

Subsection 111(5) of the Act

Subsection 111(5) denies the carry-forward of non-capital losses if control of a corporation is acquired by a person or group of persons. However, if the corporation continues to carry on the business in which the losses were sustained, the losses can be applied against income from that business or a similar business in post-acquisition years.

The new business of investing in high-yield debt instruments clearly bore no resemblance to Lossco’s former business of pharmaceutical research. The issue in dispute was therefore whether or not Matco had acquired control of Lossco as a result of the Investment Agreement.[8]

De jure and de facto control:

Subsection 111(5) restricts a corporation’s ability to deduct non-capital losses after an acquisition of control by a person or group of persons. But what does “control” mean?

While the word “control” is not defined in the Act, the SCC has concluded that it means de jure control: the ownership of such a number of shares as carries with it the right to a majority of the votes in the election of the board of directors.[9] This is the test that applies for purposes of subsection 111(5).

In 1988, the concept of de facto control was introduced in the Act:[10] where the expression “controlled, directly or indirectly in any manner whatever,” is used in the Act, a corporation is considered to be controlled by another corporation, person or group of persons, where the controller has any direct or indirect influence that, if exercised, would result in control in fact of the corporation.

At the heart of de facto control, as with de jure control, is the notion of control of the affairs of a corporation through control of its board of directors: however, the de facto control test is much broader, and includes factors that go well beyond share ownership. A number of provisions in the Act were amended so that the de facto control test would apply, such as the associated corporation rules: however, the new test was not adopted for purposes of subsection 111(5).

In its reasons for judgment, the SCC stated that adopting the broad test of de facto control would have captured a variety of situations far beyond Parliament’s concern for ensuring that one taxpayer not benefit from another’s losses. For example, an onerous third-party loan to help a distressed corporation reorient its business could create a relationship of dependence sufficient to trigger the de facto control test, even if the creditor’s influence was never exercised. However, the court added, it does not follow that the rationale of subsection 111(5) is fully captured by the test of de jure control.

The SCC decision

In a 7 to 1 decision (the majority opinion written by Justice Rowe), the court upheld the decision of the Federal Court of Appeal that the transactions were abusive and that the GAAR applied to deny the tax benefits.

The SCC stated that the parties agree that there was no acquisition of de jure control for purposes of subsection 111(5) adding that, in a GAAR analysis, the impugned transactions necessarily comply with the provision in question, properly interpreted and applied.

The issue in dispute was therefore whether the GAAR applies to deny the tax benefits. The court concluded that the GAAR did apply because, through a complex series of transactions, the taxpayer underwent a fundamental transformation that achieved the outcome that Parliament sought to prevent, while narrowly avoiding the text of subsection 111(5). As a result of the Investment Agreement, Matco acquired the functional equivalent of de jure control.

In reviewing the object, spirit and purpose of a provision, the SCC stated it is critical to distinguish the rationale behind a provision from the means chosen by Parliament to give effect to that rationale. For subsection 111(5), Parliament has chosen de jure control as a reasonable marker for situations in which tax losses are to be restricted: however, the test of de jure control is primarily a means of giving effect to Parliament’s aim, rather than a complete encapsulation of the aim itself. The key question is what the provision is intended to do: understanding a provision’s purpose is central to a GAAR analysis.

The SCC stated that a purposive analysis permits courts to consider legislative history and extrinsic evidence. In the case at hand, the legislative history of subsection 111(5) started in 1958, when restrictions on the trading of loss corporations were first put in place. While the means Parliament has chosen to address loss trading has evolved over time — finally settling on de jure control — its rationale for including the non-capital loss restriction in the Act has been consistent.[11]

The SCC said there may be circumstances where a provision’s underlying rationale is no broader than its text, but such was not the case here. The SCC summarized the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5) — its rationale — as follows: to prevent corporations from being acquired by unrelated parties in order to deduct their unused losses against income from another business for the benefit of new shareholders. The transactions clearly frustrated the rationale of subsection 111(5) and therefore constituted abuse.

The dissent:

As she is wont to do,[12] Justice Côté wrote a dissenting opinion. Justice Côté disagreed with much of the majority’s analysis, stating that the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5) is to restrict the use of tax attributes following an acquisition of de jure control — period, full stop.

In my view, the dissent is of little consequence: it is unlikely that, in future, courts will adopt a purely textual approach to the application of the GAAR as advocated in the dissent.

|

The decision in Deans Knight Income Corp. v. Canada was issued on May 26, 2023. Writing for the 7-1 majority, Justice Malcolm Rowe dismissed the appeal. Justice Suzanne Côté would have allowed the appeal. |

What does the decision mean?

As noted earlier, the decision is a breath of fresh air, and should strike a more reasonable balance between the rights of taxpayers to pursue aggressive tax plans, and the ability of the Crown to defend the integrity of the income tax system.

The courts had started to favour a textual rather than a purposive approach in the application of the GAAR. For example, in the SCC’s recent 6-3 decision in Alta Energy,[13] the majority stated that “where tax provisions are drafted with ‘particularity and detail’, a largely textual interpretation is appropriate in light of the well-accepted Duke of Westminster principle that taxpayers are entitled to arrange their affairs to minimize the amount of tax payable.”

The SCC’s decision in Deans Knight represents a fundamental change in applying the GAAR, by prioritizing the underlying rationale of a provision rather than slavishly following its text. The SCC affirmed the Duke of Westminster principle, but added that the principle has never been absolute. The court stated that the GAAR does not displace the principle in cases of legitimate tax planning: rather, it recognizes a difference between legitimate tax planning — which represents the vast majority of transactions — and planning that abuses the rules of the Act and undermines the integrity of the tax system.

As a result of the decision, taxpayers must now think more carefully before entering into an aggressive tax plan that might arguably frustrate the underlying rationale of the relevant provisions of the Act. Doesn’t this add some uncertainty? Of course it does, and that is a good thing. As Chief Justice Noël of the Federal Court of Appeal said in Foix,[14] “an anti-avoidance measure will necessarily raise question marks in the minds of those who choose to test its limits.”

This decision, and the proposed amendments to the GAAR introduced in the 2023 federal budget, are welcome and positive developments that should shift the dividing line — at least to some extent — between acceptable and unacceptable tax avoidance.

Footnotes

[1] Deans Knight Income Corp. v. Canada, 2023 SCC 16.

[2] Subsection 111(5) of the federal Income Tax Act; RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended (referred to in this article as the “Act”).

[3] Section 245 of the Act.

[4] Immediately prior to the execution of the Investment Agreement, a holding company wholly-owned by Matco’s managing director purchased 100 shares of Lossco from Newco for $10, to seek to ensure the Investment Agreement would not constitute a unanimous shareholders agreement.

[5] The reasons for judgment do not state why this transfer did not result in a taxable benefit to Newco. One possible answer is that the transfer was governed by subsection 84(2) of the Act, and resulted in a deemed dividend to Newco sheltered by subsection 112(1).

[6] This sequence of transactions ensured that Matco did not acquire de jure control of Deans Knight at any time.

[7] The IPO did not result in an acquisition of control of Deans Knight, because there was no group of post-IPO shareholders acting in concert that collectively had control.

[8] The carry-forward of SR&ED expenditures and investment tax credits are restricted in the same manner under subsections 37(6.1) and 127(9.1). Since a violation of the GAAR under subsection 111(5) would lead to a similar determination for these other provisions, the SCC based its analysis on the restriction for non-capital losses.

[9] Duha Printers (Western) Ltd. v. Canada, 98 DTC 6334.

[10] Subsection 256(5.1) of the Act.

[11] The SCC also noted that section 256.1 of the Act, enacted after the transactions at issue, includes a deeming rule for substantial equity acquisitions, adding that “consideration of a provision enacted subsequent to the transactions at issue is neither necessary nor warranted in this case”.

[12] See “Justice Suzanne Côté’s Reputation as a Dissenter on the Supreme Court of Canada”; Vanessa A. MacDonnell; The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 88 (2019).

[13] Canada v. Alta Energy Luxembourg S.A.R.L, 2021 SCC 49.

[14] Foix, Souty and Lebel v. Canada, 2023 FCA 38.

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm, and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. Author photo courtesy Allan Lanthier. Images: iStock.

(0) Comments