Trump, tariffs and Canadian tax strategies: There must be 50 ways to leave your country

Allan Lanthier explains how some Canadian corporations have redomiciled to the United States and why there may be more to come unless changes are made

|

Allan Lanthier, a retired partner of an international accounting firm, has been an adviser to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. |

DONALD TRUMP has started a trade war, with tariffs that can change on a moment’s notice. One of his goals is to convince the world — friends and foes alike — to transfer business investment, production facilities and jobs to the U.S., and there have been media reports suggesting that some Canadian companies have been doing exactly that.

For example, Shopify Inc., Canada’s largest software company, and Brookfield Asset Management (“BAM”), an investment firm, have both moved their corporate headquarters to New York. Other companies may be shifting manufacturing and production to the U.S.: and if tariffs become permanent, Canadian manufacturers with a predominant U.S. consumer base will have to consider mothballing some Canadian plants and acquiring new production facilities in the U.S.

And then we have Barrick Gold Corporation, a company that operates in 18 countries, which says it is considering doing the full Monty and moving its corporate domicile from Canada to the U.S. to become a U.S. publicly-traded company.[1] There are suggestions on social media that the Trump administration is aggressively recruiting other Canadian companies to redomicile to the U.S. as well.

With apologies to Paul Simon,[2] there must be fifty ways for Canadian businesses to leave this country for the U.S. in one way or another. This article reviews some of these migration alternatives, and concludes with recommendations that might mitigate the need for some of this planning.

Change of headquarters

The United States is an economic powerhouse, with many more consumers than Canada, and a much larger pool of investors to purchase shares of public companies. It is therefore not surprising that firms like Shopify and BAM already had much of their business and many of their senior executives in the U.S., and that their shares were listed in both Canada and the U.S.

Designating New York as an executive office in U.S. regulatory filings was therefore a technique used by both companies to gain even greater access to the U.S. investor pool as well as possible inclusion in U.S. stock indexes to boost their share price. However, it is unlikely that the designations involved any movement whatever of business capital or jobs: that had already happened.

What Barrick is considering is a different kettle of fish altogether.

Redomiciling to the United States

Barrick, the largest producer of gold in the U.S., wants to redomicile in the United States as a U.S.-incorporated public company. The company says the move would give it greater access to a more efficient marketplace and, as is the case with Shopify and BAM, attract a larger pool of investors. But Barrick faces significant tax hurdles.

When a taxpayer — including a corporation — gives up Canadian residence, exit tax applies.[3] In the case of a corporation, there is a deemed year-end immediately before emigration, and a deemed fair market value disposition of each property owned by the corporation.

In addition, as a proxy for the tax on dividends that would have applied had the company liquidated instead of leaving Canada, there is a second emigration tax under Part XIV of the Act: an additional tax of 25 percent based on the amount by which the fair market value of the emigrating company’s properties exceeds the total of its liabilities and the paid-up capital of its outstanding shares.[4]

Tax losses or depressed market values can shield a corporation from Canada’s departure taxes and, as result, there have been companies that have emigrated from Canada by continuing under the laws of the United States. Encana Corporation may be the best-known example.[5]

Corporate continuance of Encana Corporation:

Encana, one of Canada’s oldest and largest energy companies, sent shockwaves through the industry when it redomiciled to the United States in 2020, dropping Canada from its name and renaming the new parent company as Ovintiv Inc. The company said the move would give it access to more investors, but industry observers also cited stringent Canadian regulations, transport constraints, and years of opposition from climate activists. The migration included the following steps.

Ovintiv was incorporated under the laws of Canada, and acquired all the Encana shares in a share-for-share exchange. The shares of Ovintiv were listed on the New York and Toronto stock exchanges, and Ovintiv continued from the laws of Canada to the laws of Delaware, resulting in the following corporate structure:

|

|

test |

Canadian-resident shareholders qualified for tax deferral on the share-for-share exchange, under section 85.1 of the Act.[6]

As a result of its continuance to Delaware law, Ovintiv ceased to be a resident of Canada, and was liable for both exit tax on any latent gain on its assets (primarily the Encana shares), as well as the secondary tax under Part XIV of the Act. However, the information circular said it was not expected that the continuance would result in any material Canadian tax.[7] The trading value of Encana shares had fallen, and it appears that the relatively low value of the Encana shares held by Ovintiv at the time of its continuance shielded it from both of Canada’s departure taxes.[8]

There is one more layer of potential tax to consider. As the reader will note from the corporate chart further above, Encana owned U.S. subsidiary companies. This type of “sandwich” structure – with a U.S. parent (Ovintiv) owning shares of a Canadian corporation (Encana), and the Canco owning U.S. subsidiary companies — results in two-levels of withholding tax when dividends are paid by the subsidiaries, and other tax inefficiencies.

While the information circular does not explicitly address this issue, it seems likely that depressed values also allowed Encana to distribute shares of its U.S. subsidiaries to Ovintiv without material Canadian tax on a latent capital gain, or Part XIII withholding tax on a deemed dividend.[9]

In summary, while Barrick and others may say they want to redomicile from Canada to the U.S., this will be easier said than done, unless the company has tax losses or has suffered declines in value.

Triangular amalgamations:

While corporate continuance is the poison of choice when redomiciling to the U.S., there are other strategies to consider.

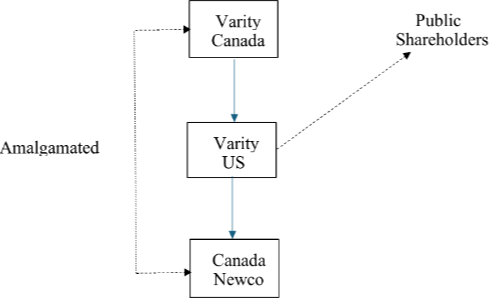

For example, in 1991, Varity Corporation (“Varity Canada”), a Canadian public company (formerly Massey Ferguson), redomiciled to the United States by way of triangular amalgamation. In overly simplified terms, Varity Canada (the publicly-traded company) incorporated Varity US in Delaware to accomplish the migration, and Varity US incorporated Canada Newco under the Canada Business Corporations Act.[10]

Varity Canada and Canada Newco amalgamated. On the amalgamation, the former shareholders of Varity Canada were issued shares of Varity US, and Varity US received the shares of the amalgamated company:

|

|

test |

As a result, Varity US became the new publicly-listed company, owning the shares of the amalgamated company.

The amalgamation of Varity Canada and Canada Newco was governed by subsection 87(1) of the Act. However, subsection 87(9), which provides a rollover to shareholders in a triangular amalgamation, did not apply because the third company, Varity US, was not a “taxable Canadian corporation”. As a result, the public shareholders would have had taxable transactions.

The amalgamated company then distributed its shares of a U.S. subsidiary corporation to Varity US as a reduction of capital (to unwind the US-Canada-US “sandwich”) and this would have been a taxable transaction as well. However, Varity’s financial fortunes had been in decline, and there was likely little if any Canadian tax payable by the shareholders or the Varity corporations as a result of the transactions.

While migration by way of triangular amalgamation avoids Canada’s exit taxes, these transactions are still only feasible for corporate groups with tax losses or value declines.

Relocation of manufacturing and production facilities

The simplest way for some Canadian corporations to address U.S. tariff issues may be to transfer manufacturing and production from Canada to a wholly-owned U.S. subsidiary. But even these transactions have tax risk.

A company that is manufacturing product in Canada for export to the U.S. may have significant amounts of goodwill such as customer lists, brand recognition, going-concern value, and intellectual property related to its manufacturing process. If a U.S. subsidiary takes over manufacturing and sales from its Canadian parent, the Canadian revenue authorities might assert that there has been a taxable disposition of goodwill.[11] After all, before the relocation there was a Canadian business earning profits and paying Canadian tax.

And so caution is required even in these types of situations.

US takeovers of Canadian companies

One of the biggest reasons for the hollowing out of corporate Canada over the last several decades has been U.S. and other foreign takeovers of Canadian businesses.

For example, assume that Canco is a public company, with wholly-owned subsidiaries in Canada, the U.S. and other countries. US Co., an unrelated corporation, makes a takeover bid to purchase all of the Canco shares for cash.

US Co. forms New Canco, and invests cash in shares of New Canco having full paid-up capital. New Canco acquires Canco for cash, and New Canco and Canco amalgamate, designating a fair market value step-up, or “bump”, in the tax basis of the shares of the subsidiaries under paragraph 88(1)(d) of the Act.[12] The amalgamated company then distributes the shares of the U.S. and other foreign subsidiaries to US Co. as a reduction of capital, with no gain realization in Canada or Part XIII withholding tax.

Canco — once a thriving Canadian-based multinational corporation — is left with only the Canadian business to serve Canadian consumers, with local managers reporting to senior executives of the new U.S. parent company.

The bump is generally not available in the context of a foreign share-for-share takeover instead of an acquisition for cash,[13] meaning the former Canadian parent would still own, and benefit from, its ownership of U.S. and other foreign subsidiaries.

Takeovers of Canadian companies by U.S. competitors or U.S. private equity firms may increase as a result of the Trump-initiated trade war, and it may be time for a legislative change to deny the 88(1)(d) bump in the context of foreign takeovers to discourage such transactions. This author is in favour of inbound foreign direct investment, but would prefer investment in new businesses to increase competition in the Canadian marketplace, rather than takeovers of existing firms.

Concluding comments

Canada’s economy has been lacklustre for years: business investment is poor as is productivity, and per capita GDP is falling. If nothing else, the trade war should knock us out of our complacency.

Canada has disadvantages — a relatively small consumer base in a geographically large country. So, how should Canada capitalize on its strengths to keep and grow businesses at home? Stephen Harper created a “Competition Policy Review Panel” in 2007 to address this very issue.

The panel’s report noted that Canada’s primary economic advantages lie in our natural resources, a diverse economy, high-quality education, and institutional and political stability.[14] And it set out a number of recommendations to build on those advantages. I have some modest recommendations of my own.

Canada needs to reduce corporate income tax for larger businesses, and provide incentives for medium-sized businesses and start-ups that have the capacity to grow. The government must eliminate interprovincial trade barriers and reduce regulatory burdens. We need more pipelines for oil and gas, and should do a better job exploring for and extracting critical minerals and processing the minerals to a much later stage in the supply chain than is currently the case. And Canadian business has to seek out foreign markets beyond the U.S., and become more innovative and entrepreneurial.

The more competitive our businesses become — and the less reliant on government subsidies and handouts — the better positioned we will be to cope with Mr. Trump’s trade war.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Last month, TFI International Inc., a Montreal-based trucking company, said it also planned to redomicile in the U.S. Under pressure from the Caisse de dépôt, one of the company’s largest shareholders, TFI has since abandoned that plan.

[8] In fact, Ovintiv recorded a tax benefit of more than US $1.2 billion in its audited financial statements as a result of the U.S. domestication.

[9] Alenco Inc. was a U.S. subsidiary of Encana. After the share exchange but immediately before Ovintiv’s continuance, Encana transferred to Ovintiv its shares of Alenco and debt owing to it by Alenco, in consideration for the assumption of Encana debt by Ovintiv and the repurchase of some of the Encana shares. These would have been taxable transactions, but Part XIII of the Act would not have applied.

Allan Lanthier, a retired partner of an international accounting firm, has been an adviser to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency.

(0) Comments