Imbalance: Accounting is not capturing the value of intangible assets

Accounting has an intangibles problem, says Nick Shepherd, author of How Accountants Lost Their Balance

|

Laura Friedrich and Brian Friedrich are the principals of friedrich & friedrich corporation. |

ACCOUNTANTS think they know about intangibles but are they things to be feared? Definitions might make us think so, describing an intangible as “impossible to touch, to describe exactly, or to give an exact value” or “influencing you but not able to be seen or physically felt.” The challenge for the accounting profession is that organizations are spending billions in creating, developing and supporting various intangibles that are strategically critical for value creation. Yet it is invisible. This is the topic of my new book How Accountants Lost Their Balance.

Because of accounting standards, most of these expenditures are considered operating expenses and are written off against income — in effect depleting equity. Yet they are core to value creation, and their nurturing, development and sustainability are critical to performance. Yet they are not considered assets. Until, of course, an M&A occurs, and the value becomes goodwill.

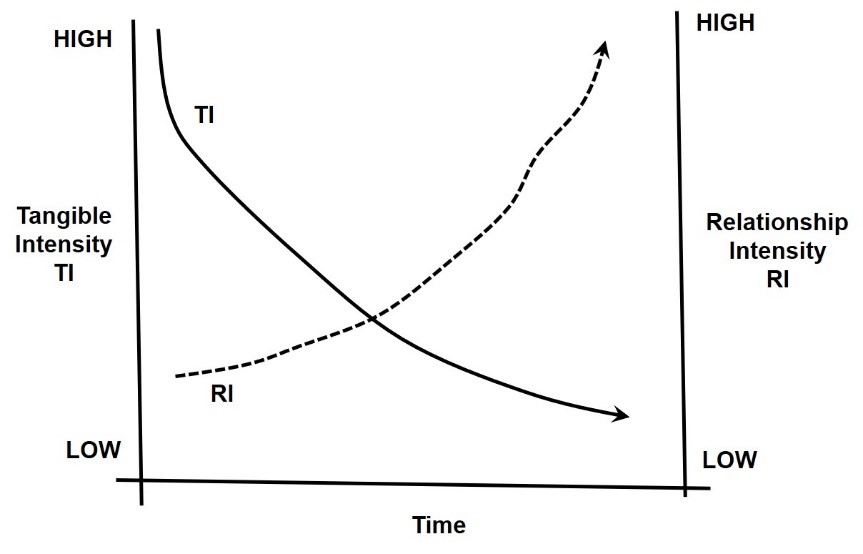

Over the course of recent business history, the tangible intensity (T1) of companies has been steadily declining, but relationship intensity (R1) has been climbing. Because accounting can “capitalize” most tangibles, these mostly appeared as assets on the balance sheet. But building relationships, internally and externally, between employees at all levels with suppliers, customers and partners, are not recognized as an asset — at least not by accounting.

|

Tthe tangible intensity (T1) of companies has been steadily declining, but relationship intensity (R1) has been climbing. (NICK A. SHEPHERD) |

The value of intengible assets continues to grow

Financial statements used to tell a good story about where the money went. The income and expense statement pretty much showed where the money went to create current income, especially when combined with the source and application of funds. The balance sheet told us where the money went that was invested in (mainly) tangible assets that would benefit income creation, into future periods.

This worked well when most expenses being paid on a “day to day” basis were incurred to create income, but that is not today’s reality. Today, a large portion of expense goes to create intangibles that benefit income in future periods. But they are not assets, and so the money being spent is charged against current income.

The result in the marketplace — the reality for the investor — is that the value depicted by a balance sheet no longer reflects anywhere near the value of the organization. Forty years ago, if I were an investor, I would typically see $0.85 - $0.90 of every dollar as an asset on the balance sheet. Today I would see about $0.05 - $0.10.

Where did the money go? Accountants may argue that it doesn’t matter as accounts are never meant to reflect value — that is the job of economists. But there are three reasons why it really does matter.

The imbalance in accounting and audit

First, audits are supposed to look at compliance, materiality, and a going concern. Today, a clean audit report may provide comfort on compliance, but ignoring the financial materiality of money directed at intangibles — and the impact these have on future value creation — leaves a large risk gap in assessing the health of the organization.

Second, when I look at the expenses charged to an income statement, these are a combination of real current expenditures, plus money directed at “future value creating” intangibles, plus money being spent to sustain and grow these value creating capabilities. As an investor I have no idea how much of my income is being spent where. As a result, profit maximization may be coming at the expense of intangible depletion, but I would never know. (Until at some future point the business model fails.)

Third, there is also no visibility of the amount of money that has cumulatively been spent in creating intangibles that are core to the ongoing creation of income, and the sustainable operation and value of the business. Each year the money been spent has been written off against income. Gone.

The result of this shift has been a decline in the value of audits as an objective assessment of organizational risk, a decline in the value of financial measurement and reporting to explain “where the money goes,” and a growing gap between accounting value and economic value. This latter point has led to a significant growth in goodwill. FASB think we have a goodwill problem; I believe we have an intangibles problem.

We cannot change our stance on standards because of the principles involved. But we can develop approaches that allow the more effective connection between the creation and sustaining of intangibles and the financial impact on the organization of creating and sustaining these. We have to get out of our traditional accounting paradigm and start leading the financial bridge building between cash flow, value and non-financial assets.

Nick A. Shepherd, FCPA, FCGA, FCCA, FCMC, is the author of How Accountants Lost Their Balance: How the Profession has Drifted Away from Reality and Must Adapt to an Intangible World.

(0) Comments