The United States has rejected the OECD minimum tax. Canada should as well – Part II

Allan Lanthier: The OECD rules were developed by committee after committee and compromise after compromise, and it shows

|

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm, and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. |

MONTREAL – The 15 percent global corporate minimum tax brokered by the OECD and championed by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has been kiboshed by Democratic Senator Joe Manchin. With the world’s largest economy and Canada’s fiercest competitor for business investment out of the deal, Canada should exit as well.

Part I of this article discussed recent developments in the US and the European Union, and set out reasons why Canada should reject the OECD proposal. This Part II is a technical analysis explaining why the OECD backstop — the “undertaxed profits rule” (UTPR) — will be unworkable should a country decide to withdraw, and why the UTPR is therefore of little relevance to Canada’s decision.

The OECD backstop and ordering rules

Some commentators say that, provided there is at least some critical mass of countries that enact the OECD tax, other countries like Canada have no choice but to proceed, even with the US out of the deal. They cite the “backstop” — the UTPR — as the reason. I disagree.

As explained below, it may be difficult or impossible for entities in foreign countries to comply with UTPR, or for foreign tax administrations to administer and enforce the rule. In addition, the extraterritorial nature of UTPR violates bilateral tax treaties.

It is true that, under the OECD model rules, if group entities in a particular country earn income with an “effective tax rate” below 15 percent, some members of the group — somewhere — are supposed to pay a “top-up tax” to make up the shortfall, provided at least one group member country has enacted the OECD rules. The OECD has included ordering rules that seek to ensure this happens.

First in line to collect the top-up tax are the countries where the low-taxed income was earned. Under the “qualified domestic minimum top-up tax” (QDMTT), low-tax countries can charge and keep the tax they helped businesses avoid. If the low-tax country has not enacted the OECD tax (or has not included a QDMTT in its rules), next in line is the country of the “ultimate parent entity” (UPE). The final backstop is the UTPR. If the country of the UPE has not adopted the OECD tax (the US for example), the top-up tax is allocated among group member entities in any country that has adopted the tax. The amount of top-up tax is allocated to all such entities using formulary apportionment, based on each entity’s relative number of employees and net book value of tangible assets.[1]

Example

Confusing? You bet it is. Here’s a simple example.

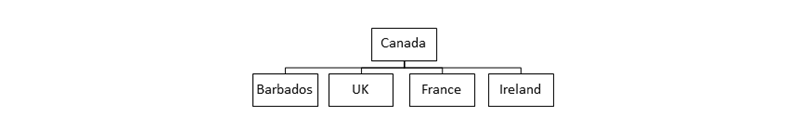

|

Courtesy: Allan Lanthier. Click on image to enlarge. |

A Canadian parent company owns 100 percent of foreign affiliates in Barbados, the UK, France and Ireland. Assume that Canada has not adopted the OECD tax, but all other countries have. Also assume that the UK has included a QDMTT in its rules.

Barbados earns royalties from the UK and pays tax of one percent.[2] The UK has an effective tax rate (ETR) of 10 percent, in part as a result of its “patent box” regime. The ETRs in France and Ireland are 25 and 12.5 percent respectively. Here’s how the rules are supposed to work.

The UK has an ETR of 10 percent and its government has adopted the QDMTT. So the UK entity owes five percentage points of top-up tax to the UK government. There is top-up tax as well for the companies in Barbados and Ireland, but the Canadian parent owes no tax — Canada has not adopted the rules. So how do we collect the tax shortfalls in those two countries? Under UTPR, we allocate the aggregate shortfall to the entities in Barbados, the UK, France and Ireland, based on the relative number of employees and net book value of tangible assets of entities in each country.

Under these ordering rules, if Canada does not adopt the OECD tax, its subsidiaries in countries that have adopted the tax should owe the same aggregate amount of top-up tax anyway, either under QDMTT or UTPR. But if the country of the ultimate parent company rejects the OECD tax (and Canada should) it may be difficult or impossible for foreign subsidiaries to comply.

The ineffectual QDMTT

The OECD tax starts with consolidated financial statements prepared by the parent company, using the accounting standard of that company: in Canada, that standard is generally IFRS. Then we need to “deconsolidate” accounting earnings, and restate accounting earnings on an entity-by-entity basis. Many of the accounting entries required to comply with IFRS may have been recorded by the parent company, and the parent must first dissect and restate consolidated earnings for each and every entity in the consolidated group.

That is just the starting point: hundreds of adjustments must then be made. The adjustments include: reinstating intragroup transactions that were eliminated on consolidation; by election, substituting accounting expense under stock option arrangements for the tax deduction in the relevant country; including deferred tax computed under IFRS depending on the nature of the timing difference, but adjusted to a tax rate not to exceed 15 percent; reversing pension expense computed under accounting standards and replacing it with the amounts contributed to pension plans for the year; and adjusting foreign exchange gains and losses attributable to differences between tax and accounting functional currencies. The list goes on.

Against this background, how can the UK group entities in our example possibly determine the amount of top-up tax they owe under QDMTT? It is the Canadian parent company that has all the records and should complete all the calculations. But Canada has not adopted the OECD tax, and the Canadian parent can hardly be expected to spend hundreds or thousands of hours each year preparing calculations for a tax regime that does not apply to it.

Without the parent company, how can the UK group entities comply? They are not privy to accounting adjustments that were made with respect to UK earnings to comply with IFRS. For example, the UK entities may not have any information regarding adjustments for deferred taxes, or foreign exchange amounts resulting from differences in tax and accounting functional currencies. And without knowing what tax the Canadian parent may have paid under Canada’s FAPI regime, they cannot even compute their ETR under OECD rules.[3]

In summary, QDMTT imposes a tax that will be impossible to compute in many situations, either by the foreign entity or the foreign tax administration. UTPR is even worse.

UTPR – the backstop that cannot be complied with or enforced

Assume that a US-based multinational has 90 foreign subsidiaries (some wholly-owned and some with minority shareholders) in 40 high and low tax countries. As explained in Part I of this article, GILTI is not OECD-compliant and so, under OECD rules (rules that have yet to be drafted), US tax on GILTI will simply be a “covered tax” which should be attributed to the relevant foreign subsidiaries around the world (article 4.3.2(c) of the model rules).

As with QDMTT, the US parent (USP) can hardly be expected to compute amounts for a tax regime that does not apply to it — computations that would include: (a) deconsolidated earnings under US GAAP on an entity-by-entity basis; (b) hundreds of adjustments to GAAP amounts under OECD rules; (c) effective tax rates, including certain deferred taxes recorded under US GAAP but adjusted to comply with OECD rules, as well as allocations of US tax under Subpart F and the non-compliant GILTI; (d) top-up tax owing by foreign subsidiaries under UTPR; and (e) finally, each subsidiary’s proportionate share of the UTPR tax using formulary apportionment.

There is no foreign or domestic law that requires (or even asks) the USP to do all this, or imposes any filing requirements on the USP. The basic filing requirement lies with the foreign subsidiaries themselves (article 8.1.1 of the OECD model rules).

Of course, if its country of residence has adopted the OECD tax, a foreign subsidiary will be required to comply with its domestic tax law, but it has none of the information that would allow it to do so. This is the QDMTT compliance disaster on steroids — a tax that cannot possibly be complied with or enforced in any sensible manner.[4]

In addition, UTPR almost certainly violates bilateral tax treaties: countries cannot impose tax on business earnings of a resident of another contracting state if the earnings have no nexus to the country seeking to impose the tax.

What about the corporate alternative minimum tax (CMT) in the US?

Here we find ourselves in yet another pickle. As discussed in Part I of this article, the Democrats will be fighting furiously over the next few days to enact the CMT — a minimum tax of 15 percent on US giants like Amazon and Nike that have annual consolidated accounting profits of more than US $1 billion. If enacted, CMT will only apply to about two hundred US multinationals. Its limited reach, and the fact that it would not be applied on a country-by-country basis, mean that CMT is not OECD-compliant as a global minimum tax. So what is it under the OECD rules?

The OECD must turn its mind to that question. Perhaps its model rules should be changed to treat CMT as a QDMTT. And, with respect to foreign subsidiaries of US parent companies, perhaps a portion of the tax should be allocated to foreign CFC’s and treated as “covered taxes” in determining their ETRs. I have practised international tax for 50 years and have never seen such a mess.

Concluding comment

The OECD rules were developed by committee after committee and compromise after compromise, and it shows. The model rules are flawed, and Canada should withdraw.

Footnotes

[1] To keep this analysis (and the example that follows) as simple as possible, I have omitted reference to “partially-owned parent entities” (POPEs) and “intermediate parent entities” (IPEs). The complete ordering for the OECD top-up tax (for countries that have adopted the tax) is actually as follows: (a) first, if the country in question has included a QDMTT in its rules, to low-taxed entities in that country (even if the country retains its low tax rate for other corporate groups that are below the threshold of € 750 million of annual gross revenue); (b) next, to entities in the country of a POPE; (c) next, to entities in the country of the UPE; (d) next, if the country of the UPE has not enacted the OECD rules, to entities in the country of an IPE; and (e) as the final backstop under UTPR, to entities in any countries that have enacted the rules.

[2] Part I of this article recommends that, instead of adopting the complex and convoluted OECD rules, Finance Canada should draft targeted changes to our tax code to address the tax avoidance loopholes that remain, including for example a repeal of subparagraph 95(2)(a)(ii) of the Income Tax Act (the “Act”). With this repeal, the royalty income earned by Barbados would be taxed in the hands of the Canadian parent company under Canada’s “foreign accrual property income” (FAPI) rules, at a rate of about 26 percent.

[3] Under Canada’s FAPI rules, the parent company may owe Canadian tax on some of the earnings of the UK entity (for example, passive income, or specified types of income that erode the Canadian tax base). Tax on FAPI paid by the parent company is added to the current and deferred tax otherwise attributable to the UK entity (in the case of “Passive Income” as defined in the model rules, in an amount that results in an ETR not to exceed 15 percent) to determine the entity’s ETR and, therefore, the amount of top-up tax that is owing.

[4] In Canada, the requirement to produce foreign-based information (section 231.6 of the Act) will be one of the many issues that arise. Under subsection 231.6(8) of the Act, if a taxpayer (say a Canadian subsidiary of USP) fails to comply substantially with such a requirement, the taxpayer is prohibited from introducing the foreign-based information in a civil proceeding relating to the administration or enforcement of the Act.

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm, and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. Top image: Modified image: iStock. Author photo courtesy: Allan Lanthier.

(0) Comments