GAAR Clips Westminster’s Wings

Vern Krishna, whose work was cited in the Deans Knight decision by the Supreme Court of Canada, explains the history of the Westminster principle and GAAR

IT IS A fundamental principle of Anglo-Canadian law that a taxpayer is entitled to arrange his or her affairs to minimize tax. The frequently cited decision is the judgment of the House of Lords in the Inland Revenue Commissioners v. His Grace the Duke of Westminster [1936] A.C. 1 (U.K. H.L.), which was the origin of the principle by the same name.

The Westminster principle is fundamental in Anglo-Canadian tax law and has been since the House of Lords decision. Over time, however, tax law balances the interest of the state in revenue collection and the private interests of taxpayers. As we have moved from the free market era of the mid-war years of the 20th century towards a more regulatory state, tax law has enacted statutory changes that circumscribe tax planning, such as, the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) in section 245, which limits the principle where tax plans are “abusive” of the Income Tax Act [ITA].

Thus, the statement that "every man is entitled if he can to order his affairs so that the tax attaching under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be" raises the inevitable question: what are the circumstances when the principle does not apply?

Background of Tax Avoidance

Canada imported the doctrine of strict literal construction from England into its common law system and applies it despite section 12 of the Interpretation Act, which deems every enactment to be remedial and "shall be given such fair, large and liberal construction and interpretation as best ensures the attainment of its objects".

Similarly, in Construction of Statutes (2nd ed. 1983), E.A. Dreidger, stated the modern rule:

Today there is only one principle or approach, namely, the words of an Act are to be read in their entire context and in their grammatical and ordinary sense harmoniously with the scheme of the Act, the object of the Act, and the intention of Parliament (at p. 87).

However, Canadian courts interpret tax law strictly and literally on the traditional constitutional theory of parliamentary supremacy in tax legislation. Canada has resisted non-formalist methods of interpretation partly, as the House of Lords remarked, due to the dominance of the accounting profession in Canadian tax law.[1]

The resilience to change is only partly attributable to the influence of the Westminster doctrine that a taxpayer is entitled to arrange his affairs under a tax statute so as to minimize tax, regardless of the purpose of the statute. The dominance of the accounting profession, untutored in the principles of statutory construction, in tax law and legislative drafting nurtured literal and strict construction. Thus, although statutory interpretation in other areas of law shifted away from the formal to purposive interpretation, tax law was left behind as an island of literal interpretation.

The Westminister principle is foundational in Canadian tax law, but subject to contrary provisions in the Act, such as, section 245.[2]

…this Court has never held that the economic realities of a situation can be used to recharacterize a taxpayer's bona fide legal relationships. To the contrary, we have held that, absent a specific provision of the Act to the contrary or a finding that they are a sham, the taxpayer's legal relationships must be respected in tax cases.

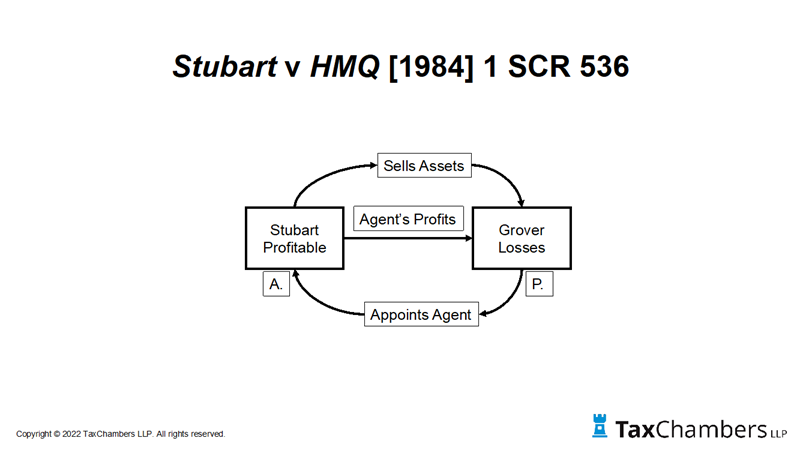

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stubart [3] was the primary impetus for the enactment of GAAR in section 245.

The facts in Stubart were simple. The taxpayer, Stubart, was a profitable business. Its sister corporation, Grover, had accumulated losses. Pursuant to amendments in 1951, the Income Tax Act prohibited the consolidation of income from separate corporate operations. To overcome the restriction on consolidation of income, Stubart sold its assets to its sister corporation (“Grover”), which had accumulated large tax losses.

|

Image provided by author. CLICK TO ENLARGE. |

Concurrent with the agreement of purchase and sale of the assets, Grover appointed Stubart as its agent to carry on the business. Stubart continued to operate the business as usual, but now only as an agent of the sister corporation. At the end of each of the relevant fiscal years, Stubart paid Grover the net income that it realized from the business. Grover, in turn, reported the income in its corporate tax returns for the relevant years. The result was to merge the profits of the profitable business with the losses of the sister corporation. The sole purpose of the transactions was to mitigate taxes through the utilization of tax losses in the sister corporation. The transfer had no other business purpose.

Section 137 of the Income Tax Act (as it read at the time), an anti-tax avoidance provision, provided in part as follows:

“(1) In computing income for the purposes of this Act, no deduction may be made in respect of a disbursement or expense made or incurred in respect of a transaction or operation that, if allowed, would unduly or artificially reduce the income”.

The Department of National Revenue reassessed Stubart, setting aside the entries transferring the net income to Grover, and charged the net income back to the Stubart’s taxable income.

However, the Crown failed to plead section 137.

“The Attorney General of Canada expressly, in response to a question from the Court during the hearing of the appeal, said that the Crown was not relying upon s. 137” (per Estey J. at p. 547).

Estey J. in obiter would likely have upheld the assessment under section 137 (at p. 547):

“Clearly the cheque transferring the profit from the appellant to Grover at the end of the year is a disbursement, and it is a disbursement the deduction of which leaves no taxable income in the appellant from the business”.

However, the Crown framed its appeal based on the absence of a "genuine business purpose" to the arrangements or the "abuse of rights" principle, which formed part of the taxation principles in the laws of the United Kingdom and the United States. The Crown argued that those laws were equally applicable in the interpretation of the Income Tax Act of Canada at the time.

The Supreme Court rejected the argument. The arrangement was valid because it complied with the technical requirements of the Income Tax Act, without the necessity of a commercial purpose. Per Justice Estey at para. 55:[4]

“I would therefore reject the proposition that a transaction may be disregarded for tax purposes solely on the basis that it was entered into by a taxpayer without an independent or bona fide business purpose. A strict business purpose test in certain circumstances would run counter to the apparent legislative intent which, in the modern taxing statutes, [we] may have a dual aspect. Income tax legislation, such as the federal Act in our country, is no longer a simple device to raise revenue to meet the cost of governing the community. Income taxation is also employed by government to attain selected economic policy objectives. Thus, the statute is a mix of fiscal and economic policy. The economic policy element of the Act sometimes takes the form of an inducement to the taxpayer to undertake or redirect a specific activity. Without the inducement offered by the statute, the activity may not be undertaken by the taxpayer for whom the induced action would otherwise have no bona fide business purpose. Thus, by imposing a positive requirement that there be such a bona fide business purpose, a taxpayer might be barred from undertaking the very activity Parliament wishes to encourage. At minimum, a business purpose requirement might inhibit the taxpayer from undertaking the specified activity which Parliament has invited in order to attain economic and perhaps social policy goals.”

Justice Estey endorsed Dreidger’s observations in the Construction of Statutes (2nd ed. 1983), at p. 87:

“Today there is only one principle or approach, namely, the words of an Act are to be read in their entire context and in their grammatical and ordinary sense harmoniously with the scheme of the Act, the object of the Act, and the intention of Parliament”.

In formulating tax interpretational guidelines, the Court said that where the substance of the Act and the clause in question is contextually construed, is clear and unambiguous and there is no prohibition in the Act which embraces the taxpayer, the taxpayer shall be free to avail himself of the beneficial provision in question (at page 581). This was, in essence, a restatement of the Westminister principle.

Thus, Stubart frustrated the Department of Finance (“Finance”), which typically curtailed tax planning through detailed and specific provisions. However, just as quickly as Parliament blocked one avenue of fiscal escape, innovative tax planners would burrow another hole in the statutory patchwork. As the General Counsel of Finance testified before the Commons Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs:[5]

“It is apparent, from looking at the kind of activity that gave rise to very specific anti-avoidance rules over the last couple of years that taxpayers are becoming a bit more aggressive than they have been historically. And that is reflected, I think in a number of ways. Obviously, the proliferation of fairly well publicized tax-avoidance schemes is evidence, I think, of the willingness of taxpayers and their advisers to undertake fairly aggressive tax planning. They do that because they examine, presumably, as advisers do, the limits that exist on tax avoidance, statutory or judicial, and they feel comfortable that within those limits they can still advise taxpayers to proceed. The result of that I think has been the proliferation of legislation, which we have seen over the last couple of years, to deal with it on a case-by-case or specific basis.”

Finance identified three problems with its specific anti-avoidance rules.

Timing: rules targeted at specific transactions typically closed the barn door after the horses had bolted and usually exempted partially completed transactions.

Complexity: specific provisions added complexity by attempting to anticipate every conceivable permutation and combination of potential tax planning that planners might use in commercial transactions.

Limited resources: in terms of intellectual energy and efficiency, the tax advisory industry is more productive than tax collectors and government policy advisors. Given the intellectual resources of Canada's legal and accounting firms, Finance needed a powerful weapon to battle aggressive tax lawyers and accountants.

Finance’s testimony before the House Committee captured its frustration:

“You could wait until [the] courts develop more sophisticated judicial limits along the lines of what the courts have done in the United States. The difficulty with that, though, is that the Supreme Court of Canada, in one case at least [the Stubart decision], looked at the existing Canadian Act, looked at the question of whether there should be a judicially introduced tax avoidance test, and said no, there exists in the Canadian Income Tax Act already a general antiavoidance rule [section 137, which the Department of Justice failed to plead] and it is therefore inappropriate for the courts to develop such a rule.

In reviewing the existing provisions of the Act, particularly the one referred to by the Supreme Court, our view is that it is not of broad enough application, as I think has been amply demonstrated over the last couple of years. If taxpayers thought the rule was that effective, we would not have had nearly the need for the kind of legislation we have introduced over the last couple of years. Obviously, taxpayers are not intimidated ....”

Following CRA’s loss in Stubart [6] in 1984, Finance continued with its practice of legislating detailed and specific anti-avoidance rules. However, four years later, it introduced the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) to control “abusive” tax avoidance (1988). GAAR marked the dawn of a new era of statutory control of tax avoidance.

Stubart was decided in 1984. Four years later, the Department of Finance enacted section 245 of the Act, the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR), to address abusive tax arrangements that contravene the object and purpose of statutory provisions whilst complying with the technical wording of the Act.

It would take another 34 years before Finance would recommend an economic substance rule along the lines in the U.S. Internal Revenue Code [see: The Department of Finance’s consultation paper released on August 9, 2022, under review and Budget 2023 proposals to amend the GAAR by: introducing a preamble; changing the avoidance transaction standard; introducing an economic substance rule; introducing a penalty; and extending the reassessment period in certain circumstances.]

Economic Substance

A rule would be added to the GAAR [245(4.1)—ed.] so that it better meets its initial objective of requiring economic substance in addition to literal compliance with the words of the Income Tax Act. Currently, Supreme Court of Canada jurisprudence has established a more limited role for economic substance.

The proposed amendments would provide that economic substance is to be considered at the ‘misuse or abuse’ stage of the GAAR analysis and that a lack of economic substance tends to indicate abusive tax avoidance. A lack of economic substance will not always mean that a transaction is abusive. It would still be necessary to determine the object, spirit and purpose of the provisions or scheme relied upon, in line with existing GAAR jurisprudence. In cases where the tax results sought are consistent with the purpose of the provisions or scheme relied upon, abusive tax avoidance would not be found even in cases lacking economic substance. To the extent that a transaction lacks economic substance, the new rule would apply; otherwise, the existing misuse or abuse jurisprudence would continue to be relevant.

The amendments would provide indicators for determining whether a transaction or series of transactions is lacking in economic substance. These are not an exhaustive list of factors that might be relevant and different indicators might be relevant in different cases. However, in many cases, the existence of one or more of these indicators would strongly point to a transaction lacking economic substance. These indicators are: whether there is the potential for pre-tax profit; whether the transaction has resulted in a change of economic position; and whether the transaction is entirely (or almost entirely) tax motivated.

The transfer of funds by an individual from a taxable account to a tax-free savings account provides a simple example of how the analysis could apply. Such a transfer could be considered to be entirely tax motivated, with no change in economic position or potential for profit other than as a result of tax savings. Even if the transfer is considered to be lacking in economic substance, it is clearly not a misuse or abuse of the relevant provisions of the Income Tax Act. The individual is using their tax-free savings account in precisely the manner that Parliament intended. There are contribution rules that specifically contemplate such a transfer and, perhaps more fundamentally, the basic tax-free savings account rules would not work if such a transfer was considered abusive.

The proposal would not supplant the general approach under Canadian income tax law, which focuses on the legal form of an arrangement. In particular, it would not require an enquiry into what the economic substance of a transaction actually is (e.g., whether a particular financial instrument is, in substance, debt or equity). Rather, it requires consideration of a lack of economic substance in the determination of abusive tax avoidance.

Supreme Court Curtails Westminster

The recent decision of the Supreme Court in Deans Knight Income Corp. v. Canada ("Deans Knight")[7] illustrates the application of section 245 and its intersection with statutory SAARs and the Westminster principle.

As noted above, since 1951, Canada has not generally permitted consolidated financial reporting for income tax purposes. Each corporate entity is a separate taxpayer and reports its own corporate profits and losses. Subsection 111(5) is an anti-avoidance provision that specifically safeguards this policy and prohibits "trading" in loss corporations upon changes in corporate "control". Control is the ownership or control in law over sufficient voting rights of the corporation's shares as would entitle the owner/controller to elect a majority of the corporation's board of directors ("de jure control").[8]

Paragraph 111(1)(a) allows a taxpayer to offset its non-capital losses by carrying them back three years and forward for twenty years as deductions in computing the taxpayer's “taxable income” in such years. In effect, a taxpayer can utilize its losses over twenty-four years, namely, the year in which the loss occurs, the preceding three years and the twenty following years. A loss that the taxpayer cannot use as a deduction in that period is lost and, to the extent unabsorbed, cannot be used to reduce the taxable income of any subsequent year.

Subsection 111(5) limits "loss trading" where a corporation acquires an entity for its unused losses and rolls over the assets of a profitable corporation into it to absorb the losses.[9] The provision is intended to prevent financial consolidation of separate corporate entities upon a change of control.

The taxpayer, Deans Knight, sought to circumvent the de jure requirement of change of control operating under the name Forbes Medi‑Tech Inc. ("Forbes"), had $90 million of unused non‑capital losses, scientific research and development tax expenditures, and investment tax credits. However, it did not have income against which to offset its losses. The corporation arranged a series of complex arrangements to utilize the losses under paragraph 111(1)(a) of the Act, but without triggering the anti-avoidance loss carryover restriction in subsection 111(5).

- Forbes moved its assets and liabilities into a new parent company, Newco.

- Pursuant to an investment agreement, Matco purchased a debenture convertible into some of the voting shares and all the non‑voting shares that Newco held in Forbes.

- While Newco was not obliged to sell its shares to Matco, it was promised that it would receive at least a guaranteed amount if it sold the shares or if such an opportunity did not present itself.

- Matco would find a new business venture for Forbes, which would be used to raise money through an initial public offering ("IPO").

- The profits from the venture could be sheltered by the tax attributes (unused losses) that Forbes originally could not utilize.

- Other than when acting pursuant to the investment agreement, Newco and Forbes could not engage in a variety of activities without the consent of Matco.

- Matco found a mutual fund management company, Deans Knight Capital Management, that agreed to use Forbes for an IPO through which it would raise money to invest in high‑yield debt instruments.

- Forbes changed its name to Deans Knight.

- The IPO and subsequent investment business succeeded.

- Deans Knight then deducted most of its non‑capital losses to reduce its tax liability in its 2009 to 2012 tax years.

Following the above series of transactions, Deans Knight transformed into a company with new assets and liabilities, new shareholders, and a new business whose only link to its prior corporate life was the tax attributes of unused losses.

- It contracted for the ability to select Deans Knight's directors.

- The investment agreement placed severe restrictions on the powers of the board of directors which, but for a circuit‑breaker transaction that occurred, would normally occur through a unanimous shareholders agreement and which would lead to an acquisition of de jure

- The transactions allowed Matco to reap significant financial benefits, while depriving Newco, the majority voting shareholder on paper, of each of the core rights that it could ordinarily have exercised.

The series of transactions technically satisfied the Westminster principle in avoiding the specific loss trading restrictions in subsection 111(5). There was no "acquisition of control" since "control" means de jure (legal) control.[10] However, an unrelated third party acquired the "functional equivalent" of de jure control by means of contractual arrangements that would not be relevant in determining de jure control.

The Supreme Court rejected the taxpayer's argument that "where Parliament has legislated with precision [subsection 111(5)], as here, where loss carryovers are denied in specific instances, the GAAR is not meant to play a role". Writing for the 7-1 majority, Rowe J. stated:

There is no bar to applying the GAAR in situations where the Act specifies precise conditions that must be met to achieve a particular result, as with a specific anti- avoidance rule [SAAR]. As the majority recognized in Alta Energy, "[a]busive tax avoidance can also occur when an arrangement 'circumvents the application of certain provisions, such as [SAARs], in a manner that frustrates or defeats the object, spirit or purpose of those provisions'…[11]

Broadly stated, s. 111(5) is a restriction on a taxpayer's ability to make use of its non-capital losses incurred in another taxation year. Three elements of the text warrant consideration: s. 111(5)'s reference to control; its focus on an acquisition by a person or group of persons; and the continuity of business exception. The appellant argues that the object, spirit and purpose of the provision is captured by the de jure control test within s. 111(5). In some cases, the object, spirit and purpose may be no broader than the provision itself. However, this is only where the text fully explains the provision's underlying rationale. To determine whether this is the case for s. 111(5), the analysis must move to the context and purpose of the provision. The appellant argues that the use of the de facto control test in other provisions indicates that "Parliament ... understood the difference between de facto and de jure control and intended that difference". For the appellant, this is effectively determinative of the dispute [.]

In my view, the context of the Act reveals that, when faced with a choice between de jure and de facto control as the general test, [.] there are various reasons why Parliament would have chosen the de jure control test as the standard [.] [I]t does not follow that the provision's rationale is fully captured by the de jure control test. Rather, de jure control was the marker that offered a roughly appropriate proxy for most circumstances with which Parliament was concerned — particularly given that the GAAR exists as a last resort. Indeed, the rationale of s. 111(5) is illuminated by related provisions which both extend and restrict the circumstances in which an [AOC] has occurred. These provisions suggest that de jure control is not a perfect reflection or complete explanation of the mischief that Parliament sought to address.

Deans Knight did not alter the legal test under GAAR. However, the decision illustrates that there is a risk if a taxpayer achieves an outcome highly similar ("functionally equivalent") to that at which a particular provision is directed, that it will fall within the legislative purpose of the provision and that GAAR will apply.

The Court's focus on the "abusive" nature of the arrangements, which circumvented the object, spirit, and purpose of preventing the loss trading rules that Parliament intended, reflects a shift towards purposive interpretation, at least in the context of GAAR. The Westminster principle was not sufficient to protect the taxpayer where it "abused" the Act.

Restrictions on Westminster

The Westminster doctrine, which has prevailed for 87 years, has invited increasingly complex and detailed legislation to counter tax avoidance. As each new scheme spawned to manipulate the literal language of the statute, Parliament responded with new SAARs and "comprehensive" legislation, such as the GAAR to thwart the tax planner's latest innovative schemes. In turn, the detail of new SAARs opened fresh opportunities for tax consultants to seize upon individual words to manipulate with literal interpretation.

There will always be some tension between a taxpayer's right to arrange her own affairs to minimize tax according to the strict legislative language of a fiscal statute and the exercise of judicial control over abusive tax avoidance that emasculates the policy of the statute. As with any maxim, the danger with the Westminster principle is that blanket reliance upon it can mislead taxpayers into believing that their tax plans are immune from attack. The maxim invites taxpayers to believe that they need attend only to the specific words of the Act without concern for the underlying policies of tax law.

To be sure, a taxpayer is entitled to arrange her affairs to mitigate tax in an acceptable and lawful manner. However, Finance increasingly erodes the Westminister principle through an increasing number of statutory anti-avoidance rules, some of which are specific, and others general. The 2023 Budget announced further proposals to strengthen purposive interpretation and weaken the Westminster principle through an economic substance doctrine, akin to the American approach of tax interpretation.

So, does GAAR trump Westminster? Yes, it can do so where tax transactions undermine the object, spirit, and purpose of specific provisions to the extent that they abuse the Act. Westminster’s wings are increasingly being clipped and will be more so when the “economic substance” doctrine is enacted into GAAR.

Footnotes

[1] Inland Revenue Commissioners v. McGuckian [1997] STC 908 (HL).

[2] Shell Canada Ltd. v. Canada [1999] 3 SCR 622 at para 39; Canada v. Antosko [1994] 2 SCR 312; Canada Trustco Mortgage Co. v R, 2005 SCC 54, para 31 and endorsed in Copthorne Holdings Ltd. v. Canada. [2011] 3 SCR 721, para 67; Copthorne Holdings Ltd. v Canada. [2011] 3 SCR 721, para 65.

[3] Stubart Investments Ltd. v. The Queen, [1984] 1 SCR 536, [1984] CTC 294, 84 DTC 6305 (SCC).

[4] Stubart Investments Ltd. v. R., 1984 CarswellNat 222, [1984] C.T.C. 294, 53 N.R. 241, [1984] 1 S.C.R. 536, 10 D.L.R. (4th) 1, 84 D.T.C. 6305, 15 A.T.R. 942, 84 D.T.C. 6323 (Supreme Court of Canada).

[5] Mr. Jim Wilson, a practising lawyer with the McCarthy’s law firm on loan to the Department of Finance.

[6] Stubart Investments Ltd. v. Canada, [1984] 1 SCR 536.

[7] [2023] SCC 16.

[8] Buckerfield's Ltd v MNR, [1964] C.T.C. 504 (Exch) , in which Jackett, P stated the view that the word “controlled” contemplates the right of control that rests in ownership of such a number of shares as carries with it the right to a majority of the votes in the election of the board of directors (ie, de jure control). The voting control test established in Buckerfield's Limited was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in Duha Printers (Western) Ltd v R, [1998] 3 C.T.C. 303, where Mr Justice Iacobucci confirmed that “section 111(5) of the Income Tax Act contemplates de jure, not de facto, control” (page 334).

[9] For example, on a tax-free rollover under subsection 85(1).

[10] Duha Printers, [1998] 3 CTC 303 (SCC). But now see subsection 256.1(6).

[11] [2022] 1 C.T.C. 271 (SCC).

Vern Krishna, FCGA, FCPA, CM, QC is a tax lawyer with TaxChambers LLP in Toronto. This article originally appeared on the website of TaxChambers LLP. Author photo courtesy TaxChambers LLP.

(0) Comments