Corporation tax: ‘race to bottom’ may be ending after 40 years — here’s why it never made sense

The Canadian corporate tax rate follows decades-long global pattern of reduction

|

Malcolm James is Head of Accounting, Economics and Finance, at Cardiff Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom. |

Cardiff – It may seem scarcely believable to younger generations that in 1981 the statutory rate of corporation tax in the UK was 52%. Certainly, generous tax reliefs meant that the tax base was relatively narrow and the effective rate was therefore rather lower, but it’s still an eye-watering number compared to nowadays. By 1997, at the beginning of the New Labour era, the rate had fallen to 31% and it is now 19%.

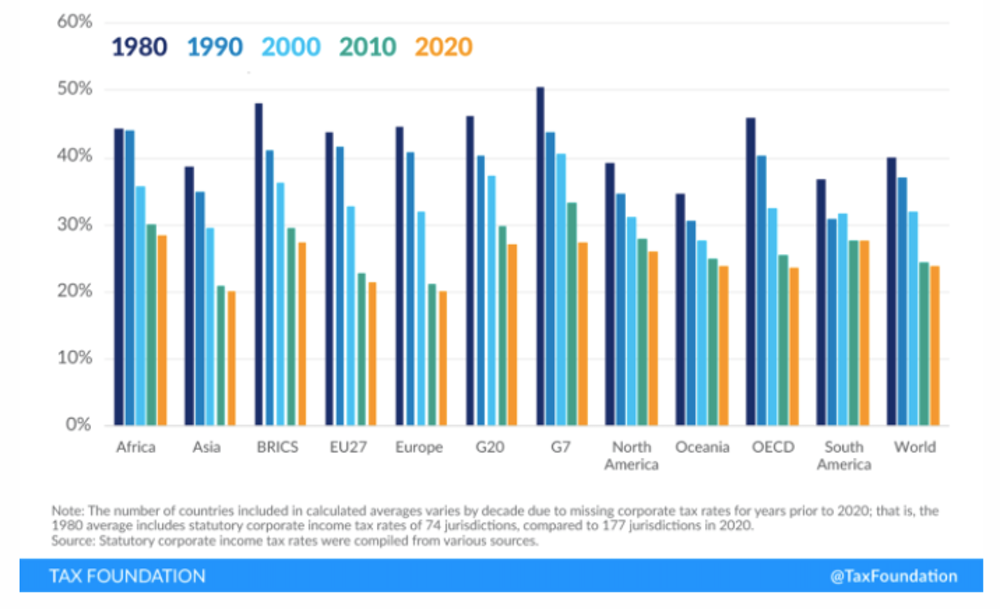

The story is similar elsewhere. In the U.S. the rate in 1980 was 46%, but had fallen to 34% by the late 1980s. It stayed at around this level until 2018, when it was reduced to 21% by the Trump administration.

Meanwhile, the OECD average rate fell from 28.6% to 21.4% in the two decades leading up to 2018. Numerous countries, including France and Belgium, cut their corporation tax rates in 2020 and France, the Netherlands and Sweden were reported in December to be planning further cuts in the near future.

Average corporation tax rate by region

|

Tax Foundation |

But the corporate tax climate may now be changing. In the UK, the Conservative government had originally planned to further reduce corporation tax to 17% in 2020. But this was shelved, and it is now reported that the chancellor of the exchequer, Rishi Sunak, is proposing to increase corporation tax in the budget — a move which promises to be very unpopular with businesses.

In the US, incoming president Joe Biden has proposed raising the rate to 28% as part of his overall package of tax reforms. This would reverse his predecessor’s 2018 reduction, although doubts have been expressed over whether he will be able to carry it out. But, after decades of global corporation tax cuts, why are we seeing signs of a shift?

[Editor's note: You can download a spreadsheet here from the Tax Foundation of corporate tax rates around the world — including Canadian corporate tax rate data — for the years 1980-2020.]

Flawed foundations

The rationale for cutting the corporate tax rate rested on a set of assumptions that have come to look highly debatable. Governments were threatened that if the rate were too high, global companies would relocate to a country with a more favourable tax regime, thereby depriving the first country of both tax revenue and economic activity. The evidence that they actually do so is mixed. For example, Accountancy Age reported that only 22 companies left the UK for tax reasons between 2007 and 2011.

At the same time, companies which move their head offices for tax purposes do not necessarily move their underlying economic activity. When Starbucks decided to move its European headquarters from Amsterdam to London in 2014, for instance, it obviously wasn’t moving the coffee shops through which it trades. It was reported that Starbucks’ move would create only a few jobs in the City of London (albeit well-paid ones), and therefore not much tax revenue.

This suggests that when companies do move offices to be more economically active elsewhere, “talent trumps tax incentives.” More than likely, taxation is of much less importance than factors such as the quality of the labour force and infrastructure.

A second argument for low rates has been that companies pass on higher taxation to their employees and/or customers, rather than reducing returns to their shareholders. In other words, there’s no point in raising business taxes because it will not come out of company profits as intended.

It is sometimes pointed out that in the UK, for example, this is unavoidable because the Companies Act 2008 section 172 obliges directors to act solely in the interests of shareholders. For this reason, directors must supposedly reduce their tax liabilities by any legal means, including passing them on to whoever they can.

However, this interpretation of the section is incorrect. It is actually much more nuanced, obliging directors to have regard to a number of factors. These include the long-term consequences of the decision, the interests of the employees, the need to foster good relations with suppliers, customers and other parties and the desirability of maintaining a good reputation.

In any case, the reality about what happens to corporation tax liabilities appears to be different. According to the American tax analyst Professor Edward Kleinbard, the US government estimates that capital — in other words the company — bears between 75% and 95% of the economic cost of corporation tax. He makes the point that “if labour bore 80% of the burden of the corporate income tax, corporations wouldn’t care about it at all.”

There is also empirical evidence that shareholders behave as if they bear the economic cost. In April 2011 the tax pressure group US Uncut and the satirical stunt specialists Yes Men issued a hoax press release purporting to be from General Electric stating that it would be making a US$3.2 billion tax “refund” as contrition for past abuses. The release, which was widely circulated before being exposed, briefly saw General Electric’s shares fall by around US$3.5 billion — roughly the amount of the hoax refund.

In short, the “race to the bottom” on corporation tax was never built on very strong foundations. It is no coincidence that the arguments supporting rate reductions have started to lose traction. During the good times, people are not too concerned about how the cake is divided up, the argument being “let’s just bake a bigger cake.”

In times of crisis, arguments about fairness and equality tend to become much more important. Even for politicians on the right and centre such as Sunak and Biden, the COVID crisis and the ensuing shock to the economy have created much more political leeway to raise rates than previously. It will be interesting to see what happens in practice in the coming weeks — and whether other major economies decide to move in the same direction.

Malcolm James is Head of Accounting, Economics and Finance, at Cardiff Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom.

(0) Comments