I lost my battle with the CRA, but I won the war

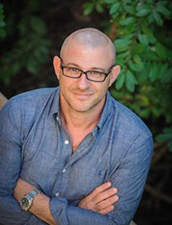

Taxpayers often lose at the objection stage, says Tax Lawyer Dale Barrett

|

Dale Barrett is the managing partner of Barrett Tax Law and a frequent tax lecturer, primarily for accountants. |

VAUGHAN – My law firm cannot make the claim that we have won all of our cases in the Tax Court of Canada, but what we can tell you is that every single case we have won in tax court — either in trial or a settlement — was lost at the CRA objection stage. And in many cases, besides losing our tax assessment objection, we were also unable to convince a CRA auditor of our client's position. In these types of cases, two different Canada Revenue Agency departments had thought we were wrong before we were able to convince a judge otherwise. So before a win or settlement in tax court, the taxpayer often has to lose twice.

After notices of objection fail, people ask us whether it is worth fighting their case in tax court. After a loss, many taxpayers simply roll over and accept that the CRA was right — but the tax agency is often wrong.

One of the key issues is that within the four walls of the CRA, the agency has a tremendous amount of discretion and there is nothing really compelling it to consider tax law. If a taxpayer provides all the receipts for their vehicle expenses but fails to keep a proper auto log, then the tax auditor can easily (and often does) deny all the vehicle expenses, notwithstanding that the Income Tax Act and the Excise Tax Act do not require taxpayers to keep an automobile log and notwithstanding the fact that the expenses were legitimate. This requirement for a mileage log is an invention of the CRA audit department and is definitely not something that is required to win or settle a case in the Tax Court of Canada. And while a business travel log provides good evidence of the division between personal and business uses of a vehicle, it is not the only means of proving one's case.

CRA auditors often use arbitrary reasons to deny expenses or to consider certain amounts as undeclared income. Perhaps it is because the tax auditors err on the side of caution to protect the agency or perhaps it is because auditors have a vested interest in making tax assessments that are as high as possible. Either way, many CRA auditors take a very conservative approach to allowing expenses. If documentation is not perfect, an auditor can simply disregard what is provided, with very little recourse available to the taxpayer except to object and eventually appeal to the Tax Court of Canada.

The underlying factor that allows us to win cases in tax court, which were lost at the tax objection stage, is that the CRA doesn't have to take into consideration the laws of evidence. On the one hand, the CRA's assessments are deemed by law to be correct (until successfully challenged by the taxpayer), regardless of how incorrect the tax assessment may actually be. So irrespective of what errors the auditor or appeals officer makes, the agency is always right. And on the other hand, tax auditors and CRA appeals officers disregard, or do not understand or choose not to uphold, the rules of evidence and, as such, give more weight to their theories and suspicions than actual evidence provided by the taxpayer.

In a nutshell, the law of evidence determines what evidence must or must not be considered by a judge. This body of law also assigns relative weights for various types of evidence: direct evidence should be given more weight than circumstantial evidence and circumstantial evidence should be given more weight than just a suspicion. Judges know this and the Department of Justice counsel know this, but to the CRA, it simply doesn't matter.

For example, if a person has no receipts from the construction of a house and the Canada Revenue Agency denies all of the building expenses, that taxpayer can go in front of a court and provide oral testimony about their expenses. They can provide other evidence, such as before-and-after pictures to demonstrate that work was done; they can bring witnesses to provide testimony; they can swear before a judge that they paid the expenses in question; and they can win their case — even without so much as one receipt. Their CRA audit, on the other hand, won't go so well without receipts — no matter how many people provide evidence to the tax auditor.

When considering the value of various types of evidence in tax court in the absence of receipts, we must remember that a witness providing oral testimony in criminal court doesn't have to provide a video or any other documents to convince a court that a murder took place. Their testimony regarding their eyewitness account is direct evidence. And unless there is conflicting evidence, they are generally taken at their word. So why should tax court be any different? The answer is that it's not.

At the end of the day, if the Canada Revenue Agency has no actual evidence to put into question the credibility of the taxpayer or their testimony provided at trial, then it has a weak case. An agency assumption based on circumstantial evidence (having a Mercedes in the driveway and only declaring $20,000 income per year, for example) will not be strong enough to trump the actual evidence. And going to trial with a weak case could cause the CRA to lose in court and possibly become responsible for court costs payable to the taxpayer.

The bottom line is that the lawyers at the Department of Justice are busy. They are well-educated and reasonable and they understand the laws of evidence. Not only are they too busy to try cases where the position of the CRA is based entirely on a theory and where the agency has no actual evidence, but their knowledge of the laws of evidence allows them to make a determination about how the court would decide the case. Unless evidence is perfect and unimpeachable, the CRA may choose to ignore it and decide the case against the taxpayer — but if counsel believes that a judge would find in favour of the taxpayer, they will typically be amenable to a reasonable pretrial tax settlement.

This analysis performed by the Department of Justice counsel is something that is not done at the CRA level, which means it is far more likely a correct outcome will be achieved when dealing with the Department of Justice than with the CRA. So remember that in tax, even if you lose and lose again, you may win in tax court. Often times where tax is concerned, three times is the charm!

Dale Barrett is the managing partner of Barrett Tax Law, founder of Lawyers & Lattes Legal Cafe, author of Tax Survival for Canadians and the editor of the Family Law and Tax Handbook. He is also a frequent tax lecturer, primarily for accountants. This article was originally published on the Lawyer's Daily.

(0) Comments