The economics professor at the centre of the Ottawa tax firestorm

As Justin Trudeau defends Morneau tax proposals in Question Period, Michael Wolfson shares his opinions with Canadian Accountant

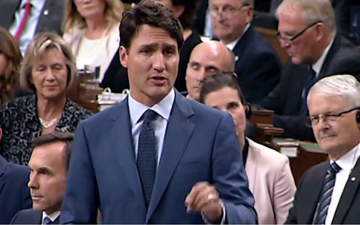

OTTAWA, Sept. 18, 2017 – As predicted Sunday night on Twitter by Canadian Accountant, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made an unexpected appearance in Question Period on Monday, despite an important visit by British Prime Minister Theresa May to discuss post-Brexit trade.

The firestorm over Finance Minister Bill Morneau's tax amendment proposals required the Prime Minister's presence to fend off a prolonged attack over the proposals by Conservative leader Andrew Scheer, who stood no less than 11 times to challenge Trudeau over taxes.

Lost in the turmoil was the academic in the eye of the hurricane. Michael C. Wolfson is a professor and researcher at the University of Ottawa whose research into income splitting was cited in the 2015 election campaign and subsequent government announcements regarding taxation. His main finding was that the growing use of Canadian controlled private corporations by some individuals to reduce their taxes was costing the federal government about a half-billion dollars per year.

Wolfson has a stellar resumé. A Ph.D. is economics from Cambridge University. Formerly the assistant chief statistician, analysis and development at Statistics Canada. Prior to joining StatsCan, he held positions in the Treasury Board Secretariat, the Department of Finance, the Privy Council Office, the House of Commons, and the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office. He is a Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and a member of the International Statistical Institute.

As Canada's independent news source for the accounting profession, Canadian Accountant is currently pursuing an interview with Wolfson, in the interest of balanced reporting. In the meantime, Wolfson offered to share two recent Op-eds with readers of Canadian Accountant, which we have reproduced, with the author's permission, below:

Should the loudest voices prevail on proposed tax reform – even if it is shrill hyperbole?

By Michael Wolfson

Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s proposals for tightening tax breaks associated with private companies is generating several kinds of response on social media and in mainstream media. The most evident is an impressive deluge of evidence-free rhetoric claiming that the proposals are an attack on everything from the middle class to maternity leave for female doctors to farmers and even mom-and-pop corner stores.

Far less visible, but probably much more important, are the number of economists and tax and accounting professionals who are taking the discussion paper seriously. Even those who may be strongly opposed to the tax tightening are offering detailed and constructive advice.

Still, almost absent in this debate are any voices defending the idea of tax fairness.

A newly formed Coalition for Small Business Tax Fairness penned a letter to Mr. Morneau opposing the tax reforms, claiming that “two-thirds of small business owners earn less than $73,000 per year and half of those earn less than $33,000.” Magicians call this “misdirection,” but in this case, let’s call it spin: The numbers are correct – they just have nothing to do with the debate at hand.

It is unlikely that the modest earners identified by the small business lobbyists will be affected at all by the proposed tax changes, though we still do not know the details of the government’s proposals. We do know from the Finance Minister’s remarks that only individuals with a private company – a Canadian-controlled private corporation, or CCPC – have even a chance of being affected.

As my colleagues and I showed in a study published in the peer-reviewed Canadian Tax Journal last year, less than 5 per cent of taxpayers in the bottom half of the income spectrum – with incomes below $27,500 – even owned one of these private companies (based on figures from 2011, the most recent year for which we had data); among those in the bottom 90 per cent – with incomes below $68,800 – less than 10 per cent had a CCPC.

Now let’s look at the top earners – people the coalition and other critics would rather we forgot. Almost half of those in the top 1 per cent, with incomes above $163,300, owned a CCPC, while more than 70 per cent of those in the top 0.01 per cent, with incomes over $2,305,700, owned one.

Requiring millionaires who use their CCPCs for aggressive tax planning to pay more tax is certainly not an attack on the middle class or mom-and-pop corner stores.

The Coalition for Small Business Tax Fairness, as well as many other, more strident voices, claims CCPC owners should also have the right to amass wealth in their private companies after paying only the 15 per-cent CCPC tax rate, then pass that wealth on to the “next generation” (their children) tax-free. But is it fair for CCPC owners to be able to multiply their lifetime $800,000-plus capital gains rollovers three or four or five times for just one business – one of the practices Mr. Morneau’s proposals seek to end? Shouldn’t one lifetime rollover be more than enough? Even one of these rollovers is a much richer tax break than people without a CCPC get. And if you do own a CCPC, you have to be rather rich to have substantial capital gains in the first place.

It is valuable to compare the public discourse on tax-rate unfairness for the rich and the poor. In the case of private companies, a number of mostly high-income individuals face the prospect that their effective marginal income tax rate may increase from 15 per cent (if they successfully sprinkle dividends to family members who will not need to pay any income tax at all on those dividends) to a maximum of about 50 per cent – in line with what all other upper-income earners who don’t own CCPCs pay on their wages, salaries and self-employment incomes.

Some tax professionals are constructing examples in which they claim Mr. Morneau’s proposals would saddle small businesses with tax rates of 80 to 93 per cent. But these examples make the ridiculous assumption that CCPC owners would not rearrange their affairs – for example, by simply paying out their private company incomes to themselves as salaries, which would bring them back to the top tax rate of 50 per cent.

On the other hand, there are hundreds of thousands of low-income seniors who face marginal income tax rates of 75 to 100 per cent and even higher – the so-called poverty trap that has persisted for decades. Where are their voices? Who is defending them?

Why are 100 per-cent tax rates OK for low-income seniors, yet many among the top 1 per cent become apoplectic when the Finance Minister proposes to bring their tax rates back in line with that of every other high-income individual?

Of course, Mr. Morneau’s proposals are still a work in progress. This is a complex area of tax law, so consultation is clearly important. But the loudest voices are not neutral. They are the ones with the strongest vested interests – and their interests do not necessarily accord with those of the people they claim to represent.

Michael Wolfson is an expert adviser with EvidenceNetwork.ca and a member of the Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics at the University of Ottawa. He was a Canada Research Chair at the University of Ottawa. He is a former assistant chief statistician at Statistics Canada.

The sky is falling on small business – or is it?

By Michael Wolfson

Federal finance minister, Bill Morneau recently released a long and nervously awaited discussion paper which was met with near apoplexy in some corners. The paper aimed at closing a number of loopholes where mainly rich taxpayers use private companies (Canadian controlled private corporations or CCPCs) to reduce their taxes compared to most Canadians whose incomes come through pay cheques or self-employment.

The proposals would fulfil a Liberal campaign promise to address unfair uses of some arcane provisions of Canada’s income tax act. In response, one tax practitioner said in a popular newsletter, “Finance Minister Bill Morneau just announced the Trudeau government's plan to destroy tax planning as we know it.” The Minister has given the public 75 days to respond.

So far, most of the comments have been rather general. One is that these provisions will hurt the middle class much more than the rich. This is clearly false, as shown in a study I published with my colleagues last year. For the bottom 50 per cent of income tax filers in 2011, those with incomes under $51,600, well under 10 per cent had a non-trivial interest in a private company. But for the top 1 per cent with incomes over $163,300, more than 50 per cent had a significant interest in a private company -- and for the top 0.01 per cent with incomes over $2.3 million, this figure jumps to almost 80 per cent.

Further, as I showed in a study published just before the 2015 election and cited in debates at the time between (then) candidate Justin Trudeau and Prime Minister Stephen Harper, federal and provincial governments were foregoing at least half a billion dollars each and every year in income tax revenues from the use of these private companies for income splitting.

Among those likely to be affected by the Minister’s proposals are higher income doctors, some of whom have even threatened to flee the country if these loopholes are tightened.

Before the Ontario budget in 2005, doctors’ spouses could not be shareholders in a private company set up to receive the doctor’s income. But as part of the fee negotiations at that time, the government of Ontario made a very obscure change to their corporate law allowing these spouses to become shareholders. This change was clearly a backdoor way to increase the incomes of doctors and their families without most of the public noticing. Even though the public remained unaware, the number of private doctor companies in Ontario, which had been rising slowly up to 2004 at under 1,500, climbed steeply after this budget in 2005 to over 16,000 in 2011 -- more than a ten-fold increase – and, according to the OMA, to over 20,000 today.

Obviously, this obscure legal change must have provided substantial benefits for so many doctors to incur the costs of setting up their own private companies. And if the Province of Ontario wants to help doctors maintain their after-tax incomes, they could always support the federal government in closing these loopholes and then use their own resulting increased tax revenues to increase their payments explicitly, through the front door, rather than hiding these very real benefits via obscure back door tax breaks.

More broadly, many in the business community and some leading economists tout the major benefits of cutting corporate income taxes to improve economic growth.

But there’s a very revealing graph in the Minister’s discussion paper. It shows that the taxable incomes of mainly larger public companies, even with all the major corporate income tax cuts since 2000, were quite stable as a percentage of GDP from 2002 to 2014. Over this same period, the percentage shares of GDP for the incomes of the self-employed fell by about one quarter. In contrast, the most dramatic growth was for small private corporations, the ones able to exploit the income splitting loopholes, whose incomes more than doubled as a share of GDP.

Was the decline in incomes of the self-employed, while the incomes in private companies nearly doubled, nothing more than an increasing number of well-advised higher income individuals learning to exploit tax loopholes? We cannot tell with the available data. But we could know if the government followed the Auditor General’s Spring 2015 recommendations to be much more open and fulsome in their public reporting on these kinds of tax provisions.

So no, the sky is not falling on Canada’s small businesses. The Minister’s proposals would clearly increase tax fairness. Indeed, the extra revenues collected from mainly higher income individuals, by bringing their effective income tax rates more in line with their salaried counterparts, could be used to benefit the poor and those in the middle class.

Michael Wolfson is an expert advisor with EvidenceNetwork.ca and a member of the Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics at the University of Ottawa. He was a Canada Research Chair at the University of Ottawa. He is a former assistant chief statistician at Statistics Canada and has a PhD in economics from Cambridge.

Colin Ellis is the editor-in-chief of Canadian Accountant.

(0) Comments