The Robillard decision: The uncertain world of death and taxes

Allan Lanthier on confusion in surplus stripping and the post-mortem pipeline, due to a recent Tax Court of Canada decision

Montreal – Nothing is certain but death and taxes.[1] While this may be true, the manner in which tax applies in Canada on the death of a taxpayer is anything but. The decision of the Tax Court of Canada (TCC) in Robillard[2] — released late last month — has added yet another layer of confusion.

This article discusses the tax rules that apply when a taxpayer dies holding shares of a private corporation, and two approaches for avoiding the double-taxation that might otherwise arise. Then, after summarizing the decisions of the TCC and the Federal Court of Appeal (FCA) in MacDonald,[3] I review the Robillard decision and its relation to MacDonald.

The death of a taxpayer

In general terms, when a taxpayer dies, she has a deemed fair market value disposition of her capital properties, and the person who acquires the assets on death (initially, the taxpayer’s estate) has a tax cost equal to fair market value.[4] If the capital properties are shares of a private corporation, there is no addition to the paid-up capital (PUC) of the shares on death: as a result, double-taxation becomes an issue.

For example, assume that Ms. A, a resident of Ontario, owns all the shares of Co. A. The shares have a fair market value of $100,000 but no tax basis or PUC. Co. A holds cash and investments with a value of $100,000. Under her Will, Ms. A has left the shares to her son, Mr. B, who is also resident in Ontario.

Ms. A passes away. If she is in the top-rate bracket, the tax on the $100,000 gain on her final return will be 26.77 percent.[5] If Mr. B liquidates Co. A in future to access its cash and investments, he will be taxed on a deemed dividend of $100,000, and will owe additional tax at a rate of 47.74 percent.[6] Unless Mr. B can apply the capital loss that results from the liquidation against other capital gains,[7] the combined tax to Ms. A and her son will be 74.51 percent.

How can taxpayers avoid this double-taxation? The two most common methods are elections under subsection 164(6) of the Act and post-mortem pipelines.[8]

Subsection 164(6)

When capital gains tax was introduced as part of 1971 tax reform, Parliament addressed the issue of double-taxation on death by also introducing subsection 164(6). Using our example above, if the executor causes Co. A to liquidate within 12 months following the death of the taxpayer, the estate will be taxed on a deemed dividend of $100,000. However, the estate will also realize a capital loss of the same amount, which can be carried back and applied against the gain reported in the final tax return of the deceased taxpayer. The result is combined personal tax of 47.74 percent, not 74.51 percent.

Subsection 164(6) (rather than the pipeline described immediately below) is the appropriate alternative from a tax policy perspective. Corporate income tax serves a withholding function, as a backstop to the personal income tax. Under Canada’s integration regime, a corporation’s after-tax earnings are supposed to be taxed as dividends to the individual shareholders at some point.

On the other hand, there are practical issues with subsection 164(6). First, it may be difficult to comply with the 12-month requirement if there are disputes with creditors or beneficiaries: however, subsection 164(6) could be amended to allow for a period longer than 12 months. Second, a liquidation of a private corporation may not be feasible if the deceased was not the sole shareholder: but a pipeline also faces hurdles in these circumstances.

The post-mortem pipeline

As corporate tax rates declined in the 1990s, the tax cost of dividends (including deemed dividends arising as a result of subsection 164(6)) increased, and tax planners turned their thoughts to ways to eliminate any second-level of tax completely. And thus was born the pipeline.

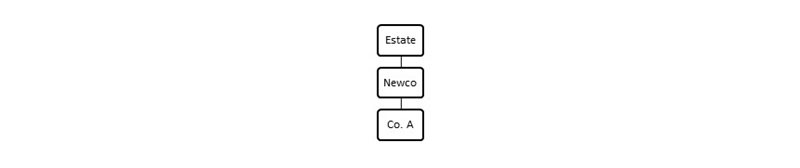

Returning to our example, the estate forms a new corporation (“Newco”), and sells the shares of Co. A to Newco in exchange for a promissory note of $100,000. The structure is now as follows:

|

Click on image to enlarge. |

The sale of shares of Co. A to Newco for a note of $100,000 does not trigger a gain or loss to the estate as it had full tax basis in the shares of Co. A. In addition, there is no deemed dividend under section 84.1 of the Act.[9] The cash and investments are now paid from Co. A to Newco as a dividend, and then to the estate as a repayment of the promissory note. Like magic, the additional tax has disappeared. The only tax is the 26.77 percent that applied on the final return of Ms. A. The estate can now distribute the cash and investments to Mr. B without further tax.

So what’s the catch?

In summary terms, subsection 84(2) of the Act states that, if funds or properties of a corporation are appropriated for the benefit of its shareholders on the winding-up, discontinuance or reorganization of its business, there is a deemed dividend to its shareholders. And that certainly seems to be what happened here — the property of Co. A was appropriated for the benefit of the estate.

However, in an advance tax ruling in 2002, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) took the position that, provided the relevant corporation (in our example, Co. A) remains in existence and continues to carry on investment activities for a period of at least one year after the sale of its shares to Newco, neither subsection 84(2) nor the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) would apply to a pipeline.[10]

This CRA position still applies today, and has been confirmed by many more advance rulings. As a result, post-mortem pipelines (with a one year holding period) are now commonplace, with the result that the tax rate on death for an individual in the top personal rate bracket is restricted to 26.77 percent. In other words, shareholder-level tax at dividend rates is routinely avoided, thanks to the one year, bright-line test the CRA adopted to provide certainty to taxpayers.

We are about to get to the Robillard decision. But first it is important to review the court decisions in MacDonald.[11]

The MacDonald decisions

Dr. MacDonald (Dr. M) was a medical doctor practising in New Brunswick through a wholly-owned professional corporation (PC). PC had cash of about $500,000 from its after-tax professional earnings. Dr. M decided to move to the United States. Of course, he could have caused PC to liquidate, paid Canadian tax on a deemed dividend of $500,000, and then emigrated. But his advisors came up with a different plan.

Dr. M had a chat with his brother-in-law (BIL), a chat that led to the following transactions. Dr. M sold the shares of PC to BIL for a $500,000 promissory note. BIL then incorporated a Newco, and sold the shares of PC to Newco for a second note. Within a matter of days, PC paid cash dividends to Newco, Newco used the cash to repay the second note to BIL, and BIL repaid the promissory note owing to Dr. M.

The result? Dr. M had the cash of $500,000. Dividend tax was avoided. And in addition, Dr. M had capital losses from other sources to shelter his gain on the sale of the PC shares to BIL. Bingo — no personal tax whatever. However, the Minister took the position that subsection 84(2) applied and that Dr. M was deemed to have received a taxable dividend of $500,000.[12]

As summarized further above, subsection 84(2) states that, when funds or properties of a corporation have at any time been distributed or appropriated in any manner whatever to or for the benefit of its shareholders, on the winding-up, discontinuance or reorganization of its business, there is a deemed dividend to its shareholders. The Minister took the position that Dr. M had appropriated PC’s cash, and that subsection 84(2) applied.

The TCC disagreed. The court concluded that the note that Dr. M received from BIL was not property of PC, and that Dr. M received the cash in his capacity as creditor, not as a shareholder of PC. The court noted that subsection 84(2) applies where there has been an appropriation “at any time”, and that Dr. M was not a shareholder of PC at the time he received the cash. The TCC found in favour of the taxpayer, and the Crown appealed to the FCA.

The FCA had a very different view. It concluded that the TCC had construed the provision much too narrowly. The provision refers to an appropriation “in any manner whatever.” Who initiated the transactions, and who ended up with the cash when the smoke had cleared? While Dr. M received the cash at a time when he was no longer a shareholder of PC, the winding-up of a business is a process, not a single event that happens at any one point of time. Applying a textual, contextual and purposive analysis, the FCA concluded that Dr. M had received a deemed, taxable dividend.

Which brings us to Robillard.

The Robillard decision

Robillard involves a post-mortem pipeline gone awry.

Mr. Robillard passed away on June 18, 2012, owning all the shares of an investment company (“Gesco”). Mr. Robillard’s Will left the Gesco shares to his three children. Mr. Robillard was taxed on a capital gain on his final return, and the Robillard Estate became the sole shareholder of Gesco. The three children formed Newco and, on January 17, 2013, the estate sold the Gesco shares to Newco for a promissory note of $1,587,866. The following day, Gesco liquidated and transferred all its investments to Newco. Finally, Newco distributed $1,564,000 to the estate in February, as a repayment of the note.

Say what? Gesco liquidated one day after its shares were sold to Newco? Since 2002, the CRA’s position has been that, provided a company remains in existence for a least one year and has investment activities, subsection 84(2) will not apply. Did the tax advisors simply blow it?

Timing is everything

The TCC had issued its decision in MacDonald on April 17, 2012, two months before Mr. Robillard passed away. In that decision, the TCC had opened the floodgates to surplus stripping. Subsection 84(2) did not apply, it said, if a taxpayer (such as the Robillard Estate) received payments as a creditor, and at a particular time when it was no longer a shareholder. It seems that the tax advisors took the TCC as the final word on this matter.

The Robillard surplus strip occurred in January and February, 2013. Then, on April 25, 2013, the FCA reversed the TCC’s decision in MacDonald. As it is difficult or impossible to distinguish the planning in Robillard from that in MacDonald (even though only one involves a surplus strip following death) the Robillard plan was doomed. Still, the taxpayer appealed and went to court.

The reasons for judgment in Robillard

In Robillard, Justice Hogan discusses, and takes issue with, the analysis and conclusions of the FCA in MacDonald. Hogan concludes that the words “at any time” are clear, and that the Robillard Estate was not a shareholder of Gesco at the time it received the distribution. But these are precisely the issues the FCA considered in MacDonald. Justice Hogan had no choice but to reluctantly find in favour of the Crown, stating that only the FCA can reconsider its analysis.

The concern of Justice Hogan seems to be that double taxation can arise on the death of a taxpayer. But was this even the case in Robillard? At paragraph 39 of the judgment, Hogan states that the CRA has apparently undertaken to allow a capital loss to be carried back to the final return of the deceased should subsection 84(2) be found to apply. This undertaking does not seem unreasonable: the executors of the estate did complete the transactions described in subsection 164(6) within the first 12 months following death. The result therefore seems to be single taxation, not double, and at the appropriate dividend rates.[13]

On balance, should the Robillard decision be appealed, there seems to be little reason for the FCA to reverse its own analysis. But stranger things have happened.

Predictability, certainty and the Duke of Westminster

In the recent 6-3 decision of the Supreme Court in Alta Energy,[14] the majority states, in its first sentence, that “The principles of predictability, certainty, and fairness for the right of taxpayers to legitimate tax minimization are the bedrock of tax law.” It continues at paragraph 29 by stating that “…where tax provisions are drafted with ‘particularity and detail’, a largely textual interpretation is appropriate in light of the well-accepted Duke of Westminster principle that ‘taxpayers are entitled to arrange their affairs to minimize the amount of tax payable’…”. While the Duke is alive and well in Canada, he is dead or on life support in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.[15]

Any time you hear a court argue for predictability and certainty (as the SCC did in Alta Energy, and the TCC in Robillard), you know that its focus will be on a textual approach that favours the taxpayer. This recent trend of the Canadian courts may not strike an appropriate balance between the rights of the Crown and those of the taxpayer, and should be of concern to us all.

Footnotes

[1] This quote is often attributed to U.S. statesman Benjamin Franklin, from a letter he wrote to a colleague in France in 1789. However, the phrase had first been used in a play written in 1716.

[2] Robillard (Succession) c. La Reine, 2022 CCI 13.

[3] MacDonald v. The Queen, 2012 TCC 123, and The Queen v. MacDonald, 2013 FCA 110.

[4] Subsection 70(5) of the federal Income Tax Act: RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended (referred to in this article as the “Act”). There is generally a rollover if properties are bequeathed to the taxpayer’s spouse or to a spousal trust.

[5] The federal-Ontario rate in the top bracket is 53.53 percent, and the tax on the taxable half of the gain is therefore 26.77 percent.

[6] This rate assumes that the deemed dividend is a “non-eligible dividend”, and that Mr. B is in the top personal rate bracket.

[7] As Mr. B had a tax basis of $100,000 in the shares of Co. A, and received a deemed dividend rather than proceeds of disposition, he should realize a capital loss of $100,000 on the disposition of the shares.

[8] Oher post-mortem planning, such as “bumps” under paragraph 88(1)(d) of the Act, are beyond the scope of this article.

[9] A deemed dividend to the estate under section 84.1 is based on the amount of the promissory note it received ($100,000), less the greater of the PUC of the shares of Co. A (zero) and their tax basis to the estate ($100,000).

[10] CRA document no. 2002-0154223(F). This ruling was followed by another in 2005 (2005-0142111R3(F)), in which the CRA again ruled that subsection 84(2) would not apply provided the one year holding period was respected.

[11] Supra, footnote 3.

[12] The Minister also applied the GAAR. As GAAR was not addressed by the FCA, it is not discussed in this article.

[13] This conclusion does not account for a deduction of $759,000 that the TCC allowed the estate under subsection 104(6) with respect to distributions to beneficiaries during 2013. Assuming that the 2013 taxation year is statute-barred for the three beneficiaries, the pipeline transaction may conceivably have resulted in complete non-taxation to the extent of $759,000.

[14] Canada v. Alta Energy Luxembourg S.A.R.L, 2021 SCC 49.

[15] See for example “Duke of Westminster: Its Evolving Influence Over the Years”; Jessica Bishara; Canadian Tax Focus, Volume 12, No.1, February 2022; Canadian Tax Foundation.

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm, and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. Top image combines iStock and author photo.

(0) Comments