Oh, what a tangled web: The taxation of foreign affiliates

Allan Lanthier examines a dispute before the Tax Court of Canada involving Brookfield Corporation and controlled foreign affiliates in Bermuda and Barbados

|

Allan Lanthier, a retired partner of an international accounting firm, has been an adviser to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. |

IN THE best of circumstances, the rules governing foreign affiliates are among the most complex in the Income Tax Act.[1] And the more complicated a corporate structure, the more challenging an analysis of foreign affiliate transactions becomes.

This article comments on a dispute that is before the Tax Court of Canada involving a structure in which partnerships were interposed between a Canadian corporation and its controlled foreign affiliates (“CFAs”), and the CFAs realized foreign accrual property income (“FAPI”).[2]

The dispute

Brookfield Corporation (“Brookfield”) is a publicly-traded Canadian corporation which, through a number of tiered partnerships, owned CFAs in Bermuda and Barbados. In 2014, certain CFAs in Bermuda realized FAPI of about $73 million, approximately $20 million of which was attributable to Brookfield’s 28 percent indirect interest. In the same year, a CFA paid dividends of about $459 million to a partnership, approximately $127 million of which was Brookfield’s 28 percent share.

As explained further below, had Brookfield held the CFAs directly instead of through partnerships, it would have been taxable on the FAPI of $20 million. However, the taxpayer’s position is that, as a result of the interaction between the rules in the Act and its regulations relevant to foreign affiliate surplus accounts, and section 96 of the Act relevant to partnerships, the FAPI is not taxable. Not surprisingly, the Minister disagrees.

Before discussing the dispute, let’s summarize some of the basic foreign affiliate rules.

The taxation of foreign affiliates

Assume for purposes of the comments in this section of the article that a Canadian corporation (Canco) owns 100 percent of the shares of a CFA.

Dividends paid by the CFA:

Dividends that Canco receives from the CFA are included in income,[3] and deductions in computing taxable income then apply depending on the surplus accounts of the CFA out of which the dividends are prescribed to be paid.[4] In general terms, dividends are prescribed to be paid first out of exempt surplus to the extent available, then out of hybrid surplus, taxable surplus and, if there is still a residual amount, out of pre-acquisition surplus.[5] However, there are a number of rules that can change this ordering, including the “pre-acquisition surplus election” in regulation 5901(2)(b) to the Act.[6]

While this article does not describe the different surplus account computations, note that (a) taxable surplus includes undistributed FAPI, and (b) pre-acquisition surplus is a notional account for which no computations are made.

Exempt surplus dividends give rise to full deductions under section 113 of the Act; deductions for dividends paid out of hybrid and taxable surplus depend in part on the amount of underlying foreign tax applicable to the surplus account balances; and dividends paid out of pre-acquisition surplus are fully deductible in computing taxable income.[7]

The FAPI rules:

In general terms, FAPI of a CFA includes passive investment income, as well as certain types of income earned by a CFA where the corresponding deduction erodes the Canadian tax base.

Unlike business income earned by a CFA (where Canadian tax consequences are deferred until the CFA pays dividends to its Canadian shareholder), FAPI realized by a CFA is included in Canco’s income on a current basis,[8] whether or not the CFA pays dividends out of the taxable surplus represented by the FAPI. In short, FAPI is always taxable to Canco in the year the FAPI is realized.[9]

The tax consequences that apply if the CFA pays dividends to Canco in the year the FAPI is realized or in a subsequent year depend on the surplus account out of which the dividend is paid. If, under the surplus account ordering rules, the dividend is prescribed to be paid out of taxable surplus, the dividend is included in Canco’s income, but a full deduction then applies under subsection 91(5) of the Act. This deduction for “previously taxed FAPI” ensures that FAPI is only taxed once – not a second time when the taxable surplus dividend is paid.

The analysis is different if the CFA has surplus account balances in addition to the taxable surplus represented by FAPI. For example, if the CFA pays a dividend out of exempt surplus, the taxable surplus balance simply remains intact in the CFA to be dealt with at a later time.[10]

Foreign affiliates and partnerships

Now, the gruesome part — the part that is in dispute in the Brookfield file: how do the rules work when a partnership is interposed between the Canadian taxpayer and the CFA? In the case of Brookfield, the condensed corporate structure was as follows:

|

As noted earlier, Brookfield is a publicly-traded Canadian corporation. “P” is a partnership governed by the laws of Bermuda (referred to hereafter as the “Partnership”), and “Bermuda” is a CFA resident in Bermuda.

In 2014, Bermuda and certain of its wholly-owned CFAs realized FAPI, $20 million of which was attributable to Brookfield’s 28 percent interest. Also in 2014, Bermuda paid dividends to the Partnership — $127 million being Brookfield’s 28 percent share.

Attribution of FAPI:

A partnership is not a person under common law, and is generally not considered to be a person or a taxpayer under the Act. However, under section 96 of the Act, if a taxpayer is a member of a partnership, the taxpayer’s income or loss is computed as if the partnership were “a separate person resident in Canada”, and each partnership activity, including the ownership of property, were carried on by the partnership as a separate person. As a result, the taxation of FAPI in the Brookfield structure is relatively straightforward: the $20 million of FAPI realized by Bermuda and its wholly-owned CFAs in 2014 was included in the Partnership’s income and was taxable to Brookfield.

The payment of dividends from a CFA to a partnership is another matter altogether, and an extraordinarily complex one at that.

The dividends paid by Bermuda to the Partnership:

The general rule in the Act and its regulations is that foreign affiliate surplus accounts only exist with respect to corporations resident in Canada. In the Brookfield structure, Bermuda is a foreign affiliate of the Partnership but not of Brookfield. As a result, in the absence of special rules, the 2014 dividend payments of $127 million would have been income to the Partnership and fully taxable to Brookfield as general foreign-source income. But there are two competing – and very different – rules that change this result.

Regulation 5900(3):

The first rule — regulation 5900(3) — relates to dividends paid by a CFA that has realized FAPI in the year or a previous year. As foreign affiliate surplus accounts only exist with respect to Canadian corporations, reg. 5900(3) says that, if a person resident in Canada receives a dividend from a foreign affiliate, for the purposes of subsection 91(5) of the Act (the deduction for previously taxed FAPI), the dividend is prescribed to be paid out of taxable surplus. This regulation applies to the Partnership, because partnerships are deemed to be persons resident in Canada under section 96 for purposes of computing income.

This means that the dividends of $127 million paid by Bermuda to the Partnership were deemed to be paid out of taxable surplus, but only for purposes of subsection 91(5). Regulation 5900(3) is intended to avoid the double taxation of FAPI: the dividends received by the Partnership resulted in a subsection 91(5) deduction of $20 million that was attributed to Brookfield.

Section 93.1 of the Act:

Regulation 5900(3) eliminates the double taxation of FAPI by deeming dividends paid to a partnership to be from notional taxable surplus. But what about the more general question: the characterization of foreign affiliate dividends paid to a partnership as being out of exempt, hybrid, taxable or pre-acquisition surplus for purposes of deductions available under section 113 of the Act to the Canadian shareholder? Until 1999, there were no rules.

Section 93.1 was added to the Act effective in 1999 and, in general terms, provides that, for purposes of certain provisions of the Act including section 113, a Canadian corporate shareholder with an interest in a partnership is considered to own the underlying foreign affiliate shares.

As a result — and while the full amount of $127 million was deemed by reg. 5900(3) to be paid out of notional taxable surplus for purposes of subsection 91(5) - for purposes of section 113 of the Act and determining Brookfield’s taxable income, the same dividends of $127 million were deemed by section 93.1 to be paid to Brookfield out of Bermuda’s actual surplus accounts following the normal ordering — exempt surplus, then hybrid, then taxable, and finally pre-acquisition surplus.

(I warned you that these rules are complex.)

The taxpayer’s notice of appeal does not mention which foreign affiliate surplus accounts were relevant for the dividend payments from Bermuda. However, the Crown’s reply states that the dividends were prescribed to have been paid out of Bermuda’s exempt and pre-acquisition surplus balances (both of which give rise to full deductions under section 113 of the Act). This seems odd considering that Bermuda had just realized FAPI of $20 million which increased its taxable surplus balance.

Perhaps Bermuda had a pre-existing taxable deficit of at least $20 million that eliminated its balance of taxable surplus. It is also possible that Brookfield made a pre-acquisition surplus election under regulation 5901(2)(b):[11] while the election is not available if a Canadian corporation is a member of a partnership that owns the CFA, there may be some arguments that this restriction does not apply in a tiered partnership structure such as Brookfield’s.

Had Bermuda paid taxable surplus dividends of $20 million to the Partnership, there would likely be no dispute before the tax court. Brookfield’s foreign affiliate dividends would have included an amount of $20 million with no relief under section 113 (other than perhaps for a small amount of foreign tax). In this event, Brookfield’s taxable income from the transactions would have been $20 million, the same amount it would have had if it held the Bermuda shares directly.

The competing arguments

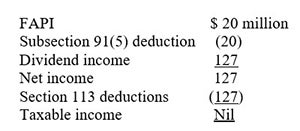

In its appeal, the taxpayer says, in essence, that it is simply applying the (somewhat conflicting) rules in the Act. Applying sections 93.1 and 96, Brookfield had the following income and deductions:

|

| image |

The result is no tax on the FAPI.

We finally get to the crux of the dispute. Paragraph 93.1(2)(d) of the Act limits the section 113 deduction to the amount of the dividends included in Brookfield’s income under section 96, which the taxpayer argues is the full amount of the dividends.

The Crown takes a different view: it agrees with the above amounts, except for the amount deducted under section 113.

Its appeal states that the deduction under subsection 91(5) only arose because Bermuda paid dividends to the Partnership. As a result, and applying the sourcing rules in sections 4 and 96 of the Act, the amount included in Brookfield’s net income as dividend income for purposes of the paragraph 93.1(2)(d) limitation was only $107 million, because the subsection 91(5) deduction should be applied to that source. With a section 113 deduction of $107 million, Brookfield’s taxable income is $20 million.

It is not obvious which side will prevail. It is clear that, under the Act, FAPI should be taxed in the year it is earned: allowing a deduction under subsection 91(5) without reducing the section 113 deduction (the taxpayer’s position) means that FAPI will escape tax.

On the other hand, the plain text of paragraph 93.1(2)(d) must be part of the analysis. When the provision was originally drafted, it seemed clear that the section 113 deduction would apply on a net basis (the Crown’s position). However, further to submissions received from (what is now) the Joint Committee on Taxation of the Canada Bar Association and CPA Canada, the language in paragraph 93.1(2)(d) was changed before enactment, in an apparent effort to allow section 113 deductions on a gross basis, this so Canadian corporate shareholders could deduct expenses such as financing costs incurred by partnerships for the purpose of earning foreign affiliate dividends.[12]

The change in wording was subtle, and whether the apparent effort to frame the limitation as a gross income test was successful will be for the courts to decide, based on the text, context and purpose of the relevant provisions: and also considering that subsection 91(5) creates a notional deduction under the Act — it is not an actual, out-of-pocket expense incurred by the Partnership, as envisaged by the committee and presumably by Finance Canada.

A taxpayer should not escape tax on FAPI as a result of faulty drafting by Finance Canada. However, in the 2010 Federal Court of Appeal decision in Exida.com,[13] the court stated that:

“The question which arises in this appeal is whether this fundamental drafting error can be cured by the purposive interpretation proposed by the Tax Court Judge. In my respectful view, it cannot.”[14]

Conclusion

The courts will determine the outcome of this dispute. However, the analysis above illustrates how unacceptably complex the foreign affiliate surplus account rules have become.

In my view, the rules have run their course. Under 1971 tax reform, exempt surplus generally only included business income earned by foreign affiliates in “listed countries” prescribed by regulations to the Act. Today, exempt surplus includes business income earned in any country with which Canada has a tax treaty (and to entities and income that enjoy special tax preferences in those countries), and to business income earned in tax haven countries as well, the only requirement being that the country have a tax information exchange agreement with Canada.

As a result, dividends out of hybrid or taxable surplus are generally paid to Canada by oversight, not design. And the rules are getting worse, not better. In 2013, the government enacted a massive technical bill with many changes to the foreign affiliate rules and regulations, many of which had been proposed ten years earlier. And now the government proposes new definitions of “foreign accrual business income” (“FABI”) and FABI surplus, for Canadian-controlled private corporations and Substantive CCPCs.

Enough is enough: we have a jungle of convoluted and at times incompressible rules that do very little to protect the Canadian revenue base. It is time to repeal all of these rules and regulations and adopt a full exemption regime: the only exception should be one simple rule attributing FAPI of a CFA to Canadian shareholders. Now there is some tax simplification for you!

FOOTNOTES

[1] The federal Income Tax Act; RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended (referred to in this article as the “Act”).

[2] As those terms are defined in subsection 95(1) of the Act. The definition of CFA first requires that the foreign entity be a “foreign affiliate” as defined: as the tax dispute described in this article involves CFAs, this article generally uses the term “CFA”.

[3] Subsection 90(1) of the Act.

[4] Section 113 of the Act.

[5] Regulation 5901 to the Act.

[6] See for example “The Preacquisition Surplus Election: More Than Meets the Eye?”; Tim Fraser and Jim Samuel; Canadian Tax Journal 2021, Issue No. 2; Canadian Tax Journal; Canadian Tax Foundation.

[7] Pre-acquisition surplus dividends reduce the tax basis of the CFA shares on which the dividends were paid. However, the tax consequences of dividends paid out of pre-acquisition surplus are much more complex when a partnership is interposed between a Canco and a CFA.

[8] Subsection 91(1) of the Act.

[9] However, effective after 2011, if there is a dispute between a taxpayer and the Canada Revenue Agency regarding whether an amount realized by a CFA is FAPI or not, the CRA – at its option – can assess FAPI either currently under subsection 91(1) or as part of a taxable surplus dividend paid in the year or in any subsequent year. See “FAPI or Taxable Surplus Dividend”; Allan Lanthier; Canadian Tax Highlights 2015; Canadian Tax Foundation.

[10] In the alternative, regulation 5900(2) allows Canco to elect, in its tax return for the year in which the dividend was received, that the dividend be prescribed to have been paid out of taxable surplus rather than exempt surplus.

[11} Supra, footnote 6 and accompanying text.

[12] For a detailed history and analysis of these issues, see “Non-Corporate Vehicles in the Foreign Affiliate Context”; Tina Korovilas and Drew Morier; 2018 Conference Report; Canadian Tax Foundation.

[13] Exida.com Limited Liability Company v. The Queen; 2010 FCA 159.

[14] Ibid., at paragraph 28.

Allan Lanthier, a retired partner of an international accounting firm, has been an adviser to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency. Title image: iStock 467135748. Author photo courtesy Allan Lanthier.

(0) Comments