The myth of CERB forgiveness

Critics of CERB forgiveness miss the point, says Allan Lanthier, FCPA, FCA

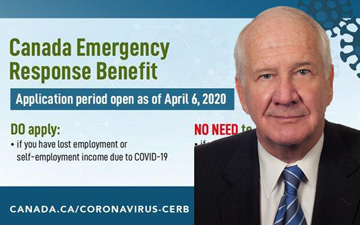

Montreal – The Canadian federal government’s recent announcement that it will administer the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) on the basis that the $5,000 income requirement is gross income before expenses prompted a barrage of criticism. Commentators say that the government should not simply ignore the law and forgive amounts that are legally owing. These criticisms miss the point: the correct legal test under the CERB Act is indeed gross income.

Is the CERB test gross or net income?

One of the requirements for CERB eligibility is that an individual earned at least $5,000 in “total income” from employment or self-employment in 2019 (or in the 12 months preceding the CERB application date). But does “total income” mean income before or after expenses?

When CERB applications opened on April 6, 2020, call centre agents at the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) had been told that the answer was gross income. In late April, this position changed to income after expenses. CRA officials have not issued even one sentence setting out a technical basis for this new position since that time. This silence is not surprising: the CRA’s position has little merit.

Total income under CERB means gross income

First, the CERB Act is separate legislation from the Income Tax Act (ITA) or any other act, and does not define “total income”: we must therefore look elsewhere for guidance. Looking to tax legislation, it is true that the term “income” generally means income after expenses under the ITA, but that is because of specific definitions, none of which apply here. In situations where those definitions do not apply, the term “income” has been interpreted to mean gross income.

For example, interest expense is deductible under the ITA if borrowed funds are used for the purpose of earning income. In a 2001 decision, the Supreme Court of Canada stated that, under this provision, income means gross, adding that, if Parliament had intended that income mean net income, “it could have expressly said so.”1

The ITA also has penalties if a person fails to report an amount that is required to be included in income. The CRA’s position is that “income” under this provision again means gross income.2

Second, Parliamentary intent is relevant under any legislation when the meaning of a term is not clear. The best evidence of Parliamentary intent in this case is the testimony of former Finance Minister Bill Morneau before the Senate in March 2020, one day after the CERB Act was approved by the House of Commons. Mr. Morneau stated that “people only have to go online to satisfy some very limited conditions saying that they have had $5,000 in revenue over the last 12 months.”

Third, the Interpretation Act governs the interpretation of every federal law in Canada, including the CERB Act. One provision in that act states that every law is deemed remedial, and shall be given “such fair, large and liberal construction and interpretation as best ensures the attainment of its objects.” Interpreting the term “total income” under the CERB Act to include an unstated requirement to deduct expenses would undermine the purpose of the legislation — to grant benefits to those in need.

Finally, we have plain old common sense. The ITA and its regulations are more than 2,000 pages long, and hundreds of those pages set out what expenses may or may not be deducted, over what period of time, and with what conditions or exceptions.

The CERB Act on the other hand does not contain a single reference to expenses. So if expenses are relevant, exactly what expenses are we referring to? As one example out of thousands, if a self-employed florist purchases a van for deliveries, the purchase price is a capital outlay — not an expense: and without any rules, depreciation expense cannot be relevant either. There is only one conclusion to be drawn: the CERB Act does not have a single rule governing expenses because the test is gross income.

Conclusion

In short, the suggestion that CERB debt is being forgiven is a myth. Many individuals — including professional advisors — treated the CRA position as if it were law: it is not. By adopting gross income as the test, the government is simply respecting the law that it enacted, to the benefit of many self-employed individuals.

Footnotes

1. Ludco Enterprises Ltd. et al v. The Queen; 2001 SCC 62.

2. CRA documents 2009-0328171I7 dated June 25, 2009, 3M05251 dated January 12, 1993, 9401865 dated May 16, 1994, and 2018-0786101I7 dated February 12, 2019. In these interpretations, the CRA draws a distinction between amounts included in computing income versus amounts deducted therefrom. Similarly, the CERB Act limits the amount of income that an individual can “receive” during any 14-day period to $1,000, with no reference to amounts “paid.”

Allan Lanthier is a retired senior partner of an international accounting firm and has been an advisor to both the Department of Finance and the Canada Revenue Agency.

(0) Comments