How government deficits fund private savings

A look at Liberal deficit spending through Modern Monetary Theory

TORONTO, March 28, 2019 – The ruling Liberals have tabled another deficit budget. The government debt grows larger. Commentators are wringing their hands and wagging their fingers. The worries are largely based in misrepresentation or ignorance of government debt and money.

The received wisdom on government debt is that it saddles future generations with the burden of repayment. The received wisdom is wrong. As long as a government’s debt is denominated in its own currency, repayment is never a problem. Why? Because the government can always create the necessary funds.

A sovereign government’s debt is one source of a country’s currency. National governments literally spend money into existence.

Deficits can cause problems, but to properly understand those problems, we have to understand the role that government finance plays in a country’s monetary system.

Government Financing 101

The Canadian government finances deficit spending by borrowing money. Twenty per cent of the money is borrowed from the Bank of Canada (BOC). In other words, the government borrows that money from itself.

The borrowed money is recorded as a debt on the government’s account and an asset on the BOC’s account. As a Library of Parliament brief on the process states, the “Bank of Canada creates money through a few keystrokes.” It adds that “there is no external limit to the total amount of money that the Bank of Canada may create for the federal government.” The government could just as easily borrow from itself 100 per cent of the deficit funds.

Deficits fund savings

Not only do governments create money in order to fund their budget deficits, the government’s debt becomes the financial wealth of the private sector.

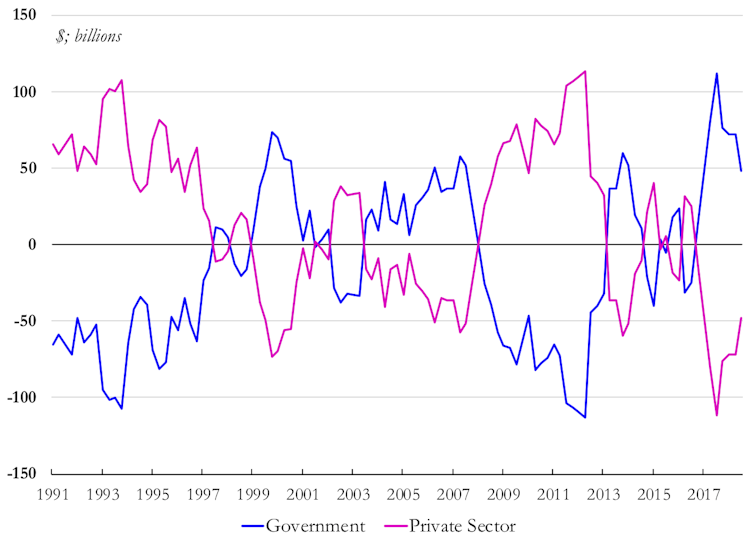

Annual Change in Financial Assets, 1991-2018

Source: Cansim table 36100580. ‘Private sector’ aggregates data for ‘Households and non-profit institutions serving households’, ‘Corporations’ and ‘Non-residents.’ ‘Governments’ is ‘General governments.’ Note: Series is the year-over-year change in quarterly values.

Source: Cansim table 36100580. ‘Private sector’ aggregates data for ‘Households and non-profit institutions serving households’, ‘Corporations’ and ‘Non-residents.’ ‘Governments’ is ‘General governments.’ Note: Series is the year-over-year change in quarterly values.

Changes in the financial assets of the government and the private sector mirror each other. Government debt equals private sector financial assets, by definition.

When the government posts a deficit, the private sector’s financial assets increase. When the government posts a surplus, the private sector’s financial assets decrease.

In other words, when the Canadian Taxpayers Federation hauls out their debt clock, showing the federal government’s increasing debt, they are also showing the private sector’s increasing financial wealth.

Separating the description from prescription

The theory describing how money works in sovereign currency countries is called Modern Monetary Theory or MMT. Many critics of MMT confuse description and prescription.

Some of the people most associated with MMT, such as academic Stephanie Kelton and U.S. congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, make policy prescriptions on the basis of MMT insights.

The most prominent example is a call for the U.S. government to fund an ambitious Green New Deal to move to a post-carbon economy. But this is distinct from the content of MMT, which describes how the money of sovereign currency countries works.

When deficits become problematic

One of the straw arguments against MMT is that its proponents claim deficits do not matter. That is completely wrong. Deficit spending puts money into the economy. When more money chases after the same number of goods or assets, the result is inflation, which can have deleterious effects. However, fear of inflation is vastly overblown.

Critics of MMT typically invoke a few historical instances of hyper-inflation. Venezuela, Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic are their mantra. However, these events occurred in completely different economic contexts where production had collapsed. Besides, inflation is primarily a function of unequal economic power. Economic power allows some businesses to continually raise prices and not others.

Taxes offer a solution to inflation. Because governments create money, they do not need taxes to fund programs. Instead, taxes are used to remove from the economy some of the money chasing after goods. Although some MMT proponents advocate redistributive taxation, that is a prescription rather than a description.

One legitimate concern of deficit hawks is that partisan governments will use their spending power for partisan purposes. The repayment myth has constrained such abuse. However, we cannot properly manage the government’s unique spending power if we do not start from a basic understanding of money and government debt.

What it all means

We need to closely examine what governments are and are not funding. A Financial Times article about MMT recognized that the United States government operates as MMT theorizes. It just uses that spending power to fund a bloated military instead of transitioning to a post-carbon economy.

When the federal government deflects calls to fund certain programs with a claim that they cannot afford it, they are misleading us. They can afford it. They are choosing not to fund it.

Consider the issue of on-reserve water quality. The Liberals promised to deal with the widespread and long-standing problem of poor-quality water in First Nation communities. However, the Parliamentary Budget Officer identified a 30 per cent shortfall in funding for dealing with the issue. As of Jan. 23, 2019, 91 communities have water advisories. Why? The funding shortfall is not because of fiscal constraints. It is a choice.

Deficit spending is not, in and of itself, a panacea to all of the issues Canada faces. The hurdles to achieving clean water for all First Nation communities are more than money. But by understanding the actual constraints on government finances, we can get past the obfuscating arguments that government debt is a burden on the future.

The tradeoff is not between the financial well-being of future generations and the current well-being of those in need. The tradeoff is between what the government is choosing to finance and what it’s choosing not to finance.

D.T. Cochrane is a lecturer in business and society at York University in Toronto. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Image by Erika Wittlieb from Pixabay

(0) Comments