Remembrance Day: Harold Garland, accountant, war hero and member of The Great Escape

Lest we forget, a profile of the late Harold (Harry) Garland, a veteran of the World War Two, who recounts his time as a prisoner of war in Stalag Luft III

Editor's Note: The following profile combines passages from two profiles of Harold Garland (1918-2009) that appeared in separate issues of "Statements," published by the Certified General Accountants of Ontario.

WHEN Harold Garland, FCGA, speaks to children about the importance of Remembrance Day, he begins with Hitler, the Second World War and The Great Escape. “Once the kids realize you were there,” he says of the infamous prisoner of war camp depicted in the classic Hollywood movie, “you’ve got their attention right away.”

Garland was born in 1918. As a teenager in the 1930s, he took accounting courses with the Credit Institute of Canada, an important institution during the 1930s due to the increase in collections during the Great Depression. He was working as an accountant and bookkeeper for Independent Electric in Toronto when World War Two was declared, and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force just days short of turning 21.

Garland flew a two-engine Vickers Wellington, a medium bomber British air forces lovingly called a “Wimpy,” nicknamed after the hamburger-obsessed J. Wellington Wimpy of the Popeye cartoons. American air forces less charitably called the Vickers Wellington a “canvas-covered coffin.”

In the spring of 1943, Garland was returning from a mission, when the plane — which had been flying askew for some time — lost altitude just before the English Channel, in Rouen, France.

Captured by the Nazis, he was imprisoned in the infamous prisoner-of-war (POW) camp, Stalag Luft III, and took part in the escape plan dramatized in the Hollywood movie The Great Escape, starring Hollywood legend Steve McQueen.

In an ambitious escape plan, the prisoners banded together to dig three tunnels that ran nine metres (30 feet) below ground.

Garland’s memories of the escapade are still vivid at age 88. “The guys had tapped into the camp’s electrical grid in order to have light in the tunnels. When the electric lights failed in the tunnels we made our own candles. The wax was made from margarine, the wicks from pyjama cord.”

Garland’s dangerous duty was that of a “penguin” — so-called for the great coats worn by prisoners to disguise the sand dug from the tunnels and hidden in bags tied to their trousers. The “penguins” would wander the prison yard and gardens, discreetly scattering sand in their wake.

150 prisoners of war, including Garland, were poised to escape Stalag Luft III on

In January 1945, fearful that approaching Russian troops would liberate the POWs, Hitler ordered the evacuation of Stalag Luft III in an attempt to keep the POWs as hostages. The forced march through snow and icy winds in the dead of winter was “harder on most of the men than our time in camp,” Garland recalled.

The evacuation lasted for three days, and included a harrowing railway ride through frozen countryside and bombed-out cities in cars that could hold 40 men but were packed with 50 to 60. Three months later, the camp to which the POWs had been transferred was liberated by American troops and Garland returned to Canada.

Life After Liberation

|

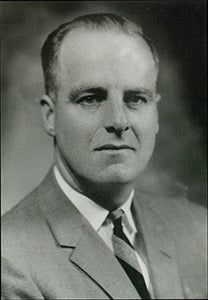

Harold (Harry) Garland, president of the Certified General Accountants of Ontario, 1959. |

At first, Garland worked as an assessor for the City of

Garland also mentions one of the benefits of the program of professional studies still echoed today by many aspiring accountants. “I was married, with children, and had a job I could ill afford to leave. CGA Ontario was very accommodating.”

In 1951, Garland earned his CGA designation. In 1959, he became just the fourth president of CGA Ontario. In 1968, he was awarded a fellowship designation by CGA Canada. In 1975, he rose to the position of assistant deputy minister of policy at Revenue

Garland takes an historical perspective in his praise of CGA Ontario’s victory in winning equal access to public accounting licences. “I was at the Public Accountancy Act meetings in 1962; naturally we were opposed to the Act. I remember leaving Queen’s Park on the day of the Legislature vote and feeling very downcast.

“I take my hat off to CGA Ontario’s executive and staff. One of the measures of success for an organization lies in taking a stand. Our leadership has been phenomenal.”

Today, Garland lives with his wife, Phyllis, in

“I worked with Tom Grandy (CGA Ontario president, 1958-59) for years,” he recalls fondly. “Tom was a wonderful guy. He’d done a tour in bomber command, but the fact is, we never talked about the war. Took me years to find that out.”

Garland adds, however, “It’s necessary to tell people that war should be avoided. It’s also true that there are times when there’s no alternative. I think Canadians understand that.”

Colin Ellis is the author of the profiles and a contributing editor to Canadian Accountant, and the former editor of CGA Ontario's "Statements" and CPA Ontario's D&A Magazine. Title image: iStock ID:2172030318 and Harold Garland.

(0) Comments